ARTG 10 - AESTHETIC DESIGNS

Module 6 - Motion, Rhythm + Animation

6.1 Introduction to Motion, Rhythm + Animation in Games + Playable Media

Movement, motion, and animation are almost synonymous with most games and playable media forms. It can be hard to imagine video games without animation and motion, as the "video" aspect was initially implemented as a technology in order to animate graphics on a screen.

That being said physical games, table-top games, cards games, etc, all also posses a sense of rhythm and motion, whether that is via the speed of gameplay, length of moves or turns, rhythm of interaction or movement across a board or in space. Digital and physical text-based games and interactive fiction also convey a sense of rhythm via multiple aspects: the actual narrative content, the rhythm of the prose, and the timing and rhythm of the narrative reveals and the player choices.

This lecture content will focus on visual motion + rhythm - both still and time-based, which I will discuss further below. The works and ideas covering visual motion below will also connect to more conceptual ideas of rhythm and time, via text and gameplay. mechanics, presented in the readings.

And, since motion, rhythm and animation plays such a crucial visual role in so many digital games and artworks, and is therefore a huge component of a game's overall visual aesthetic, this module will focus on different forms of animation, and dive into some case studies of 2D animation in games.

6.2 Basic Definitions

The definitions below are based on a few standardized definitions and principles in animation, but are much more broad. These definitions are primarily meant to establish a common language to describe and talk about motion, movement and animation in this class, at more of an introductory level. They will not conflict with any terms used to describe motion and animation in other settings, but they will probably be less specific.

Additionally, and as with the rest of the course, these categories and definitions are not strict. There will be many artworks discussed that fall within multiple classifications, and/or utilize multiple forms of motion and animation.

Motion

Visual motion is any visual change or movement in time-based artworks {4D}, or the implied sense of movement in still artworks {both 2D + 3D}.

Rhythm / Texture / Visual Quality

For this course, rhythm will be used to describe motion or movement, and how it might be perceived by viewers or players.

It can be used to describe movement or motion over short periods of time, such as fast or slow, smooth or alternating, subtle or intense, controlled or chaotic, clarifying or confusing, etc.

It can also be used to describe movement or motion over longer intervals of time, such as random, consistent, patterned, flowing or progressive.

Quick side note: Tempo is technically the term used to define speed in music, and can be used to describe speed in other applications as well, but in this class I'll be using rhythm more broadly, including to describe relative speed.

Motion Capture

I use motion capture broadly as any technique and/or technology used to somehow visually record motion occurring IRL. When I discuss contemporary motion-capture technology used primarily in film and games to map and translate an actor's movements onto a 3D model, I will be sure to specify.

Kinetic Sculptures

Kinetic sculptures are sculptural, physical artworks or spaces that include kinetic motion as a primary aspect of its overall visual aesthetic and/or expressive meaning. I am dedicating a section of this lecture to these types of artworks because they can be compelling, interactive, and highly expressive, and are sometimes overlooked in this program.

Time-Based Artworks {4D}

Time based artworks are any artworks that communicate meaning that changes over time. This is a huge subset of art, design and media, and there are some who would classify even static artworks as time-based, as they are slowly or not-so-slowly changing based on things like physical changes and/or changes in technology that shift context and meaning, but for this module, we will stick with the more straightforward defintion.

The most common time-based artworks include film, video and animation, sound art, games, performance art + some forms of interactive art/spaces and kinetic sculptures.

Animation

Animation at its' most basic level is when a series of still images are shown over time in order to create the illusion of movement. In most cases, in order to show these images to the viewer quickly enough to create this illusion, one or multiple technologies must be utilized. As I will discuss below, there is a lot of overlap between film and animation.

6.3 Image + Motion

Records of Movement

As presented in the Point, Line + Shape module, there are many artists who communicate the idea of movement via a single drawing or painting. The resulting 2D artworks contain the record of the artists' - and/or drawing implements' - movement across the canvas or drawing surface. Viewers then use these final images to compose the sense of motion or movement in their imaginations - often the aesthetic of that motion can be implied by these images as well. Is it controlled, contained, chaotic, narrative, fluid, jagged, angular, smooth, slow, fast, precise, planned, expressive, etc. Below are a few new artists and artworks that work with still images and motion that you can now also consider from this new perspective of envisioning the possible visual quality of the movement needed to create the images, as well as the movement embedded within the image itself.

Calligraphic - “Big Brush” - Painters - Liang Xiao Ping

I included the artist below in this section instead of Module 4, because their final forms also include symbolic meaning, which can directly communicate specific narrative meaning. These artworks, therefore, both create meaning via a visual aesthetic that includes a strong sense of motion, as well as a narrative component.

Cai Guo-Qiang - Records of Kinetic Energy / Moments in Time

Cai Guo-Qiang creates visuals out of the burn patterns left behind by intentionally composed combustible materials, fireworks, and other pyrotechnics. These works are both a record of a single moment in time and the record of the artists movement across the surfaces as he placed down the explosive and flammable materials. They also reveal a strong sense of visual rhythm, that is tied to the possible imagining / interpretation of the sound and audible rhythm when the physical artwork was imprinted.

Light + Motion

The artworks below utilize a technique called “light painting”. These images are produced by working with a long-exposure camera setting, and keeping the aperture lens open for long enough to track the motion of light across the frame. These paintings are interesting examples of combining light, image capture technologies, and movement in a physical space over time in a single 2D image. The light trails in these images imply a sense of speed, location, and quality of physical movement in a single, expressive frame.

Tempt One - Tony Quan

Tony Quan, also known as Tempt One, was a graffiti artist who was at the forefront of developing unique letterform styles in the 1980s and 1990s. In 2003, Tempt One was diagnosed with ALS, and lost control of most motor functions and abilities. In the early 2010’s, a team of artists, community members, and engineers came together to produce an “Eye-Writer” device and program that tracks his eye movements, outputs them to digital files which can then be projected onto architectural surface, allowing him to paint again.

The artworks he produced via this process are a record of tiny movements that are scaled up and projected in large physical spaces using light, motion tracking and image projection technologies. The action of graffiti writing is a significant part of its' overall visual aesthetic, which he was able to continue with his eyes. These artworks are a combination of many of the 4D artworks presented in this module - they work with motion capture, projection technologies and also utilize light in order to capture and project motion.

6.4 Kinetic Sculpture

Kinetic sculptures are physical artworks that are driven by movement or motion, and/or utilize movement as main form of aesthetic expression. I place artworks in this category if their meaning would dramatically change or alter if they did not move or work with motion and/or visual {and in some cases audio} rhythm.

Kinetic sculptures are similar to many of the 2D artworks viewed in class in that they exist in multiple states - they are both a static, physical object, and a dynamic physical object that reacts to a variety of inputs. The artworks contain and communicate characteristics of motion even as a still image.

These types of artworks also offer a lot of potential for audience interaction or some other kind of physical input or control to drive them and initiate movement. For these reasons especially, I wanted to include them in this section and class in general.

Theo Jansen’s Strandbeests

These kinetic forms move throughout the landscape via wind propulsion, and interact with one another and other aspects of the environment. Consider how these are constructed to created different qualities of motion and movement based on the weather, and other random physical and/or environmental impacts. I believe these artworks are so magical and amazing - their movement and motion infuses them with a sense of life, similar to how animation gives life to 2D drawings and illustrations.

collectif scale - Flux, 2021

This studio works primarily with kinetic sculptures driven by both motion, and light. These artworks connect heavily in visual aesthetic to many contemporary motion-generated still images shown above, animation, including abstract animations. These works also connect to some of the more historical motion-capture photography that will be discussed in a section below.

Zimoun

Zimoun is a Swiss artist who works with sound sculpture and architecture, but his sculptures, installations, and spaces almost equally emphasize sound. I would argue that without the visual components of objects and movement, these artworks' overall aesthetic would be very different for the audience.

Jenny Holzer

Jenny Holzer is an prolific artist who has been working with text-based sculptures and artworks since the early 1980's. Many of her earlier sculptures explored the use of light and text to communicate information in more commercial forms, such as "pre-digital" large scale monochromatic LED signs used for advertisements and/or simple scrolling text animations.

Her more recent installations incorporate more digital textual communication media, and also work with physical motion of these textual objects. The photographs taken of these sculptures in motion produce ephemeral sculptural forms via principles similar to light painting - these images then also become part of the overall installation, and are new motion-based artworks themselves.

6.5 Early Motion Capture, Photography, + Projection Technologies

Animation is a form of art and design that is inextricably linked to the technologies used to create and display it. While this is inherent to most / all forms of expressive media and art, I think it is easier to overlook things like paper, ink, paint + canvas as technologies, even though they are. Additionally, many digital artworks are produced with digital tools that correlate to a much older physical production process.

The invention and development of animation technologies intersected heavily with the development of photographic, film, and projection technologies. The first photographs were taken in the mid 1820's, and animation as we understand it first emerged in the mid to late 1800's. These mediums are, therefore, still both relatively new and technical, especially when considering the first painted artworks were created some 35,000 years ago, the first known-use of paper dates back to 200 BCE, and the letterpress was invented in 1440.

For the early engineers, scientists and artists working with motion capture technology, the cameras developed faster than the playback devices. One reason why I use the term "motion-capture" is because more modern terms like film and video imply a built-in ability to replay and watch whatever was captured. This, however, is not the case with the motion-capture technologies being developed in the 1880’s. Cameras and camera setups could "record" motion, but they couldn’t easily play it back. So, while still images were able to convey each frame of a horse’s movement in 1878, the technology to project that video wasn’t developed until more than 10 years later, and it wasn’t until 1896, almost 20 years later, that film and film-projection first started being considered more paired processes. The technologies designed to playback photographic film were derived from animation playback devices, so the two mediums had huge impacts on one another.

6.6 Early Animation Technologies

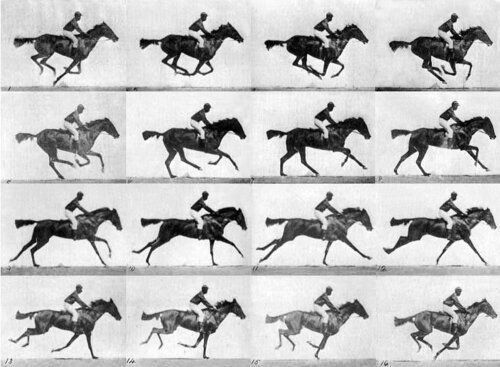

In 1878, photographer and early film pioneer Eadweard {not a typo} Muybridge developed a trigger system to photograph a galloping horse, in order to better understand the way it actually moved. Up until that point, people thought that horses moved with their front and hind legs outstretched - like the superman pose of most rocking-horses. The images of the horse in-motion that Muybridge captured - with all 4 legs in the air at once AND with them folded under the its body - was so visually shocking that people thought it was fake. So, he had to do it multiple times, and still people didn’t believe what they were seeing.

As a side note, this anecdote is a powerful statement about how much visual media informs our understanding of the world. Since horses - and many other things - move faster than human eyes can perceive, we didn't know how a lot of things actually moved until the invention of higher-speed photograph that could capture subjects in motion. For people who do not interact with horses IRL, our entire understanding of them is mediated by a visual technology.

As Muybridge became more interested in presenting these images to an audience "in-motion", he adapted an animation technology called Phenakistoscopes. Phenakistoscopes were devices that "animated" sequential drawings arranged in a circular pattern on a disc. By spinning the disc at a specific speed and isolating the individual drawings - or "frames" - via another disc with slits at a corresponding interval, these devices would animate the drawings, but could only be used by a single viewer at a time.

These animated objects have experienced a recent revival and are finding new viewers through digital animation, particularly as animated GIFs. Below are some original animated Phenakistoscope discs, as well as some modern discs, both digitally produced or physical ones designed to work with turntables and/or strobe lights.

Back in the 1890's, Muybridge further developed the technology by shining a strobe light set at a specific interval through images painted on glass discs, which would project the animations onto a screen, viewable by a larger audience. The process of embedding photos into the glass, however, distorted them so much that an artist had to re-draw them directly onto the glass, also creating one of the first rotoscopes {which will be discussed in the next section}. Muybridge dubbed this device a Zoopraxiscope, and it was the prototype for the film projectors used by Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers to publicly exhibit the first “motion pictures” in 1896. So, from one perspective, the first projected films were made possible by animation technology as well as animation techniques.

6.7 Innovation, Invention + Connections to Modern Animation

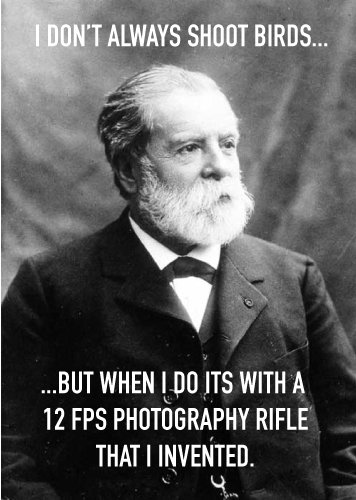

Around the same time that Muybridge developed motion-capture photography, Etienne Jules Marey, a scientist and photographer, was exploring different photographic technology and devices in order to capture movement. These invention ultimately had lasting impact on film and animation, and Marey's contributions to the art world were immense and way ahead of their time. In 1882, he designed a “Photographic Rifle” in order to film birds in flight at 12 frames per second - this is essentially the same frame rate that modern animations utilize, with some updates.

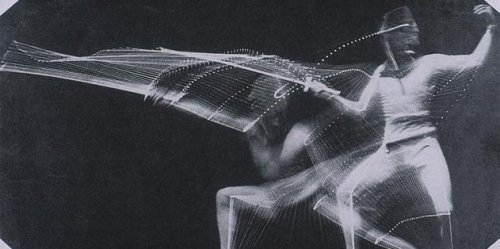

In order to exhibit and present these photographs and the motion they captured, Marey applied a photographic print process that exposed and overlayed all of the images onto a single print. While these images are “static”, they demonstrate a dynamic sense of motion and energy, similar to many of the examples in previous section and modules, but much older.

Beyond these technical advancements and designs, Marey’s conceptual approach to motion-capture and exploration of movement have interesting connections to modern animation in terms of visual aesthetics. For many of these experiments, he intentionally dressed his subjects in black, attached white stripes or other white objects in specific parts of the figures, and photographed them against dark backgrounds doing very specific actions and movements.

This design produced a highly specific visual aesthetic that was abstract, geometric, and graphic. Many of these explorations with movement are similar to the motion studies and character development that animators still work with today, or contemporary photographic "sequence shots" used to describe complicated motion and progression via a single image. The intentional framing and designed process also resemble - at the very least in concept - the modern digital Motion-Capture TM process, and Marey's photographs share visual properties with the wireframe visualizations that are often the intermediate outputs between capture and final animations.

In yet another contribution to motion and animation in art and design, Marey also pushed Zoetrope technology in new directions that directly connect to 3D animation. Zoetropes were early physical animation devices that inspired the Phenakistoscope - they would work with horizontal strips of sequenced images affixed to the inside of a drum with slits cut into it. When these drums were spun around a stick, the viewer would be able to see the animation through the slits, as they would be rotating at the same speed as the drawings. Marey created a zoetrope drum that “animated” physical, three dimensional objects - in his case, plaster birds. With this innovation, Marey, in the 1880’s, essentially developed a conceptual "proto-type" for 3D animation.

Many contemporary 3D animation studios and animation artists have recently returned to this older technological form. These artists and designers explore new visual potential in "animating" physical objects, further expanding what is possible through the use of 3D printers, projection, and vector-based light lasers. The visual aesthetics produced by these artworks are incredibly unique - mixes of digital and physical, old and new technologies, and truly enter into "magic" territory. These are also compelling examples of how the advancement of media technologies can expand spaces for new aesthetics to form from styles that were once dictated by technological limits.

6.8 Animation + Narratives

Most of the examples above communicate specific ideas, information and meaning, but mostly via the form of short, visual vignettes. Just as animation technologies developed via experimentation and innovation, utilizing animation to communicate more complex and specific narratives was a concept that formed over time.

Feel free to skip around and/or only partially watch the animations in this section. They are just there to convey a sense of the visual aesthetic and narrative expression of early animators and filmmakers.

Emile Cohl - Fantasmagorie ,1908

Artist Emile Cohle is credited with creating the first "narrative" animation in 1908. Fantasmagorie was produced by drawing each "frame" in black ink on white paper, tracing it, and applying minute changes to the next frame. Roughly 700 images were drawn, and then photographed and projected as a negative, to appear like white lines drawn on black paper - the shots in the beginning with the artists hand had to be recreated with white cut-outs on black paper and spliced into the film. The visuals are highly stylized and simple, yet still communicate a fantatsical, expressive narrative and story arch, primarily through the transformations - movements - that occur between different subjects.

Lotte Reinger - Cinderella,1922

Lotte Reinger is known as the "proto-Disney" animator because she created longer narrative animations based on well-known folk and fairy tales. Her animations did not include drawn frames, and instead worked with individual "frames" of cut-out silhouettes places on different layers of glass, compiled into a film-strip.

Since this process utilized cut-outs, the visuals were able to be more precise and detailed with less overall production time.

Indonesian Shadow Puppetry

It is important to highlight that Reinger's animations - both in visual form and narrative expression - were heavily reference Indonesian Shadow Puppet Theater. This cultural practice and art form emerged in Indonesia around 800, and was heavily developed through the 1500's. The puppets were constructed primarily from leather, and projected with light against a light fabric in a dark space - the visuals took on a highly detailed, expressive and "animated" form, long before the invention of photographic technologies. Shadow puppetry was used both as ceremonial and spiritual practice, as well as a more narrative practice.

I believe all of these origins are useful to explore and consider as a parallel to the development of video and digital games as expressive narrative formats {other than interactive fiction games}. This was not a concept or potential that was immediately apparent, and, comparatively, digital games are still very "new" forms expressive art and media. Just a good reminder that artists and designers working with games are just starting to expand what is possible, both via audiovisual expression, mechanics and gameplay, and narrative design.

6.9 Animation Categories

This section will briefly define a few broad categories and types of animation, in some cases highlighting how they have been used in games and other interactive artworks. For each of these forms, keep in mind there are a variety of methods - both digital and analog - that an artist can ultimately use to produce these different animations. As with almost everything else in this course, remember that these are just general classifications, and that there is a ton of overlap between different forms and animation processes.

Frame Animation

Frame animations are composed of thousands of still frames of drawings or paintings, each one a fraction of the movement and motion they convey. Traditionally, each frame was painted or drawn on a sheet of transparent celluloid - which is where the term “cel animation” comes from - so that animated elements could be combined and also layered on top of a static background. Each of these final frames - which might have contained multiple layers - were then composed, and photographed in order to transfer to film.

Frame Animations by Matthais Brown

Frame Animations by Penelope Gazin

Frame animation production often utilizes a pose-to-pose strategy. "Key" poses in an action or movement, such as the take-off, apex, and landing of a jump are drawn first, then intermediate or secondary drawings are added to fill in the frames based on the overall speed or timing of the action.

Pose to pose frame animations of popular Disney characters

Many 2D digital games utilize a form of "frame animation" via "sprites" - any complexly moving characters, environmental elements and/or other objects that are a part of the actual gameplay. These animations are usually implemented via a "sprite sheet", which is a compilation of each "frame" of the movement on a single bitmap-image asset.

Sprite sheet for the Drifter from Hyper Light Drifter

3D Animation

3D animation utilizes 3D objects and forms within a 3D space, "captured" via a "camera". Objects can be assigned some animated attributes that are defined via physics within the 3D environment - such as rocks rolling down a hill or hair waving in the wind, while other more complex or specific actions can be animated via keyframes and/or controls over time. Cameras can be static or animate as well.

Pixar’s first narrative 3D animated short, Luxo Jr. 1986

3D animation is utilized in most 3D games, and will be discussed more in the next content module. It can also be used to generate cutscenes, cinematics, and other scripted animations in games that do not utilize responsive 2D or 3D action. Additionally, many isometric games, such as Hades, have also started to utilize 3D animation to construct and render in-game animation and movement. The in-game space is meant to have 3D depth and perspective, and the in-game components move as if they are in a 3D space, while the game itself utilizes a 2D engine and the visual aesthetic is meant to be highly stylized with a hand-painted appearance.

Rotoscope Animation

Rotoscoping is a frame-based animation technique that traces or renders movement and motion usually filmed IRL. These traces can be very precise and representative of the original photographic images, or these original images can be used as guides for the motion they captured, and the final animation can be heavily stylized, graphic and/or more abstract. Rotoscoping can be a useful strategy for animating complexly moving subjects, such as animals or dancers, as well as complex camera movements, where the subject might be stationary but the camera is moving through a space.

The original Prince of Persia game was one of the first computer games that worked with rotoscoping to produce the art assets and sprite animations. The final in-game art was highly stylized, but the motion and animation felt incredibly realistic and expressive, especially for the time. I wanted to include this title because of the technical innovation, however, the game culturally appropriated - and then misrepresented - much of its narrative content.

Similar to the process utilized above by Hades, other games experiment with a process like rotoscoping for 2D games by creating very minimal 3D animations, applying shaders and/or other rendering effects that essentially turn the 3D animations into what looks like 2D sprites, and capturing them with a camera setup that mimics a 2D space. These animations can then be used to "reverse engineer" 2D sprite sheets and in-game 2D animations. Dead Cells utilized this process very effectively in 2019, which was originally a strategy to save on art production time and cost.

The base model used to “rotoscope” and generate sprite animations for Dead Cells

2D Vector Animation

Vector animations are generated using a keyframe process only, and transformations such as scale shifts, rotations, position changes, opacity and color changes, and even more complex motions utilizing a 2D spline or puppet-pin techniques. These types of animation often incorporate text.

This type of keyframe process uses the properties of vectors to automatically interpolate the intermediate frames between a series of manually input keyframes over time. Since vectors are infinitely scaleable, these transformations do not compromise image quality or resolution.

Some 2D digital games work primarily with vector animation, or a mix of vector and sprite animations. Many games utilize 2D vector animations in interface or HUD animations - these are often combined with - and sometimes visually overlay and/or enhance - the game's primary animation format.

Stop-Motion Animation

Stop-motion animation is a type of frame animation - it too is composed of a series of still images. Instead of drawings, stop-motion animations typically work with physical objects in a designed, scenic space. Each frame is composed, photographed, and then the objects and/or the camera are moved slightly to compose the next frame. Some of the first “special effects” in film were achieved with this stop-motion process.

When many people think of stop-motion animation, they think of claymation or puppet-animation. This style of stop motion is visually striking - it can also be a very daunting type of stop motion to start with, and it is not the ONLY kind of stop-motion, as evidenced by some of the examples below. Stop motion animation is a compelling combination of still objects and movement, and film and animation, which can produce a very unique visual aesthetic.

Games that have utilized this visual animation aesthetic and form include The Neverhood, Dominique Pamplemousse {created by UCSC DANM alumni D. Squinkifer}, and the upcoming Vokabulantis.

6.10 Animation + Games

Five Fundamentals of Video Game Animation

In traditional animation studies, there are 12 principles of animation - these are important to know and understand if pursuing animation more in-depth, but went into too much detail for this course. The video below introduces and outlines five fundamentals of game animation, from a game design / game artist perspective, which I believe is a bit more useful for this class. The Lecture Quiz will include one question about this video only.

Case Studies in Games + Animation

Choose at least one video to review. No quiz questions will be based on any of these videos.