MODULE 7: DIGITAL VIDEO + FILM

INTRODUCTION 7.1

This module we will be wrapping up the module content for the course and looking at digital film and video. I have to admit that this material was a bit daunting to develop, because digital video is a hugely expansive topic, as both an art form and a part of our contemporary digital culture and our media culture. Since it is pretty much impossible to cover this topic in a week, or a quarter, or a year, or multiple years (UCSC’s Film and Digital Media Ph.D program, for example, is designed to be completed in 6 or more years), I am going to instead present on some very specific, topical aspects, including one that relates to the this Module's exercise.

Differing from other modules, this will be less of a broad survey, and more of a zoomed-in approach. I will be discussing a few relevant ways (among many) that artists are currently engaging with the digital video format, and using digital video editors and digital video applications. I have chosen these different specifics based on not only what relates most to this course and the previous content we’ve explored, but also what is happening right now in the world of digital video and digital media (and, well, the world, in general).

7.2 DIGITAL VIDEO - The Very Basics

To preface these discussions, I want to first establish a brief timeline and define a few aspects and features of digital video that are integral to understanding how this specific technology differs from analog film and analog video in form, creation, manipulation, and distribution. This relationship between the technology and the medium - something we’ve encountered throughout this course - has a huge impact on not only how artists produce digital video and utilize different digital tools, but also what kind of artworks are produced, and the way that viewers watch, and are effected by, these artworks.

Above left to right - a late 1980's entry-level analog video camcorder and Hollywood director Michael Bay using an iPhone camera to capture video some 30 years later. Think about how these two photos might evidence how digital technology and media have changed not only how we document our surroundings but how we think about media.

Digital video and video editing tools became more accessible to individuals and artists working outside of film or video production houses starting around the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, with a few entry-level applications like Apple's Final Cut Pro and digital video cameras that still used (digital) tape, but could be connected to a computer and transfer video files via a digital cable hook up (Firewire on Apple computers) without needing a separate (and expensive) transfer set-up.

Digital video was made infinitely more accessible from 2005 - 2008 with 2 key technologies: YouTube in 2005, and the debut of portable video capture with the iPhone 3G circa 2008. Prior to these two technologies, artists and filmmakers wanting to work with digital video faced two very critical challenges.

- Digital video cameras were still very cost-prohibitive, ranging from $800 to $1500 for even the most basic devices and low quality film capture.

- Distributing (and archiving) digital video over the internet was bandwidth intensive, even for low quality videos, and it was decentralized in both format and location.

A late 1990s screenshot of the Real Player for windows - this was one app used to both play and access internet videos. Check out that amazing GIF resolution.

So, before these two technologies were developed, not only was it difficult to shoot / capture video and edit it, once something was produced, there was no way to distribute it to a wider audience (or, in most people’s cases, ANY audience). These issues have changed rapidly, and still continue to change almost daily while remaining a vital component of of the digital video medium - that is why I will be looking at streaming technology - primarily YouTube - later on.

Digital video’s digital format is another key element to remember looking at the artworks in this module. Digital video - unlike physical film or analog video tapes - can be easily edited, copied, and recombined. Additionally, digital video is convertible and - by now, at least - has a standard file type. While there are many different types of video files, and ways to compress these files (also known as codecs), most video players + editors recognize and can work with these standard sets. Finally, there are now also many processes for “digitizing” older analogue videos and films. Check out this link to the Prelinger Archive for a huge collection of digitized films. Once in a digital format, these older created works can be re-edited, or recombined.

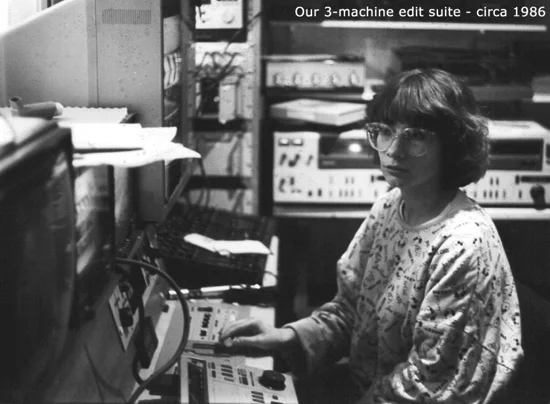

Analog Video Editing Bays - these setups were used to edit video captured on magnetic tapes through a complex process of transferring, recording cuts, then re-recording, all based on a physical timecode.

Since this field is so expansive, the majority of works in this lecture are going to be directly engaging with one or many of these key technological factors (ease of editing, ease of Distribution + streaming and relatively low cost video capture devices ). As you are viewing the works and videos below, note how each artwork, digital tool / platform or technique engages with and/or addresses these core aspects of digital video.

7.3 Digital Remix, Re-creation and Re-imagining

The digital nature of digital video allows for more accessible conversion and editing than previous video and film technologies. What was once limited to artists and filmmakers with advanced technical knowledge, high-end equipment, and access to expensive programs and tools, now can be done at a near-professional level relatively quickly and inexpensively. This expansion of video editing technology and tools has, therefore, opened up the field for more video artists to explore the idea of re-creation and the remix.

Re-creation as a method for understanding film and video artworks is something that I believe has only just starting to be explored as its own, viable art-form. Digital editing tools - as well as digital platforms for sharing and posting these artworks - have helped this practice gain legitimacy in the "art world". I have a hard time distinguishing re-creations from remixes, because they share many common principles and outcomes, but my general rule of thumb is: a re-creation builds on the narrative of the source material, usually changing it, altering it or adding to it from the outside, by merging the new artist’s ideas with those of the original piece. Remixes on the other hand, tend to first dismantle, then re-build, changing the meaning more from within. As with any of the categories I have proposed in this course, there is a ton of overlap between these two, and many artworks will exhibit components of both.

Below is a trailer for a documentary that explores a re-creation of Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark. The “fan-film” discussed was a shot-by-shot re-creation that three 11-year olds started with a Super 8 camera (non-digital) in 1982, which took more than 7 years to complete. The film itself (not the documentary) fascinates me on multiple levels - it not only tells a story similar to that of the original film, it also tells the story of the 3 young filmmakers exploring the film-making process and innovating solutions for how to re-create a Hollywood adventure movie with a tiny fraction of the resources. When viewing some of this re-creation’s footage, consider how the limited technology available to the filmmakers effects your overall interpretation of both this film, and the original.

Jumping ahead a few years, the next video artwork I’d like to discuss is a fake trailer created for Star Wars Episode II in 2002, which was posted on fan sites and movie-rumor sites (this was before the era of blogs and YouTube) a few months before the actual trailer for the film was released. This re-creation was produced with digital tools and digitized video taken from different films that had similar action scenes and/or actors slated to appear in the actual Attack of the Clones.

I remember first watching this with a feeling of excitement - even though I knew it was fake - because it hinted at narrative elements pulled from Star Wars canon that I wanted to see more of (like 4 Boba Fetts), and I had heard real film would explore. I figured that if someone could create a trailer this compelling with Final Cut 3 and a few added Lightsaber FX, the real movie was going to be amazing. After the actual trailer was released, even though it was obviously more polished, special-FX-laden and composed with footage from the actual film, I was somewhat disappointed. Part of this might have been the source material, however, I think a lot of my disappointment was that the narrative and images I had created in my own imagination - in anticipation of the actual film, fueled by a few suggestions introduced by the fake trailer - were actually more interesting than what ended up being shown in its entirety. In this way, re-creations can sometimes expand on its source material by providing alternative narrative for viewers to fill-in on their own.

An inverse of this narrative expansion through re-creation can be seen in the short film Breaking Bad: Canada Edition, below.

Here, the original narrative is re-examined and understood from a different perspective after being presented with an alternative narrative possibility. In this way, both a new story is told, and an old story is seen from a new standpoint. This type of narrative re-examination can be further pushed by viewing films or TV series through an entirely different narrative format or structure. This can happen, for example, when seeing a film as a theatrical performance, or, like in the artworks below, an 8-bit Video Game.

In the past few years, a new form of re-creation has surged in popularity - crowd-sourced re-creations. These are usually shot-for-shot recreations of films or TV series compiled from hundreds or thousands of clips - some only lasting seconds or minutes and often times produced by different filmmakers or teams. One such re-creation, entitled "Star Wars: Uncut", features entire Star Wars films recreated by hundreds of artists and filmmakers. Follow this link to view how the creators of this project were able to organize and direct crowd-sourcing in order to complete every scene.

I believe these types of re-creation films add to their original narratives by exhibiting the infinite number of ways to tell a story and exploring the viewers’ relationship to a particular story or narrative. Watching a known narrative be communicated in new ways can allow for new insights within the original story, once again changing the meaning of the original story or subject matter. Note that the film below, Star Wars Uncut: The Empire Strikes Back, is based on Star Wars V, and is posted by the official Star Wars YouTube channel even though it was generated independently of the Star Wars franchise. What is your take on this official endorsement? Does it change your interpretation of the Empire Uncut, knowing that it is supported by Disney and company?

To conclude this category of re-creation, I would like to examine 3 different video artworks that sample, reference and/or re-create existing narratives in a very interesting succession and order. Up until this point, we have been viewing works that operate within somewhat of a dichotomy - videos and films produced by relatively unknown artists and filmmakers that reference well-known film or television properties or common pop-culture narratives. The following examples offer up a bit of a reversal and also demonstrate that this practice of referencing and re-creation is not necessarily one-directional. For a truly intense viewing experience (and another level of re-creation, try playing all of these at once after viewing them separately.

Go to about 20 seconds

Go to 1:45 minute mark

Go to 30 second mark

The first video, Ever Is Over All, was created by Swiss video artist Pipolotti Rist in 1997. The second is pop singer and artist Beyonce’s music video for Hold Up, a track off of her 2016 album Lemonade. Neither Beyonce, nor the video director, have credited Rist or acknowledged pulling any kind of inspiration from Ever Is Over All, however, the visual reference is pretty undeniable even it was purely unintentional. The third video is a direct re-creation video of Hold Up produced by the team behind the Netflix series the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. In this video, actor Titus Burgess performs in full character as Tituss Andromedon, re-creating Beyonce’s Hold Up video and lyrics. The actor has clarified that the video is not intended to be parody or satire, but an homage that works within the show’s overall narrative and as a part of this character.

I think these artworks are all interesting viewing both as individual video and film artworks, and as re-created, referenced and/or inspired narratives or homages. I also wanted to post these examples to show that this concept is not limited to lesser-known artists re-creating more well-known works. When watching these videos, note your own responses and consider the following - If you had seen Ever Is Over All previous to Hold Up, did you notice the similarity? Do you think that Hold Up is less powerful after seeing Ever Is Over All, or does it change the narrative enough that it is simply an effective sample or reference? Would it make a difference if Beyonce had acknowledged the similarity or possible inspiration? Does the Titus Burgess video invoke satire, parody or homage in your opinion? Does it make this piece more or less powerful that the artists involved have expressed that it was intended to be a direct homage. And, finally, how does Burgess' video - released most recently - effect your memory or interpretation of Ever Is Over All, the oldest video of the three?

In other words, what happens when an artwork is an homage to another artwork that borrows visuals from another artwork? Does that change the original source material or narrative? Is this starting to remind anyone of Back to the Future? (if Rist hadn’t ever made Ever Is Over All, what would Tituss Burgess be acting out in the homage video?…or…would the Hold Up video even exist at all, without the Hold Up visuals that were so striking…?)

Remix, as an artistic concept and practice, is not a technique unique to digital technologies - it is essentially collage applied to sound and film, and was originally implemented using analog processes. As we discussed during Module 2, the Dada-ists developed collage as a way to destabilize, recombine and reconstruct a societal structure that had produced World War 1. The idea of remix works with these similar principles - taking apart something “known” and recombining it with different ideas to create new meanings.

Digital video editing tools have multiplied the number of artists and filmmakers working with this idea of remix. This notion of remix can be seen in clip compilations, memes, mashups and other forms of digital recombination. While these types of video collage and remix are often comical and/or absurd, consider how they also work to create completely new narratives. What kinds of stories do you find yourself creating or expanding on when viewing these types of videos? Do they change the way you understand the original tropes, styles, stories and other remixed elements?

As evidenced above, many of these remixes or mashups take on a comedic approach. Humor, however, does not negate meaning or effectiveness. To me, these achieve a special level of the absurd that is both hilarious and engaging - I am laughing, but I am also understanding the tropes and structures utilized by romantic comedies and family-friendly sitcoms in new and different ways. These videos change the way I might watch a romantic comedy in the future - if a bit of editing and a different voice over can convince me that Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter are enjoying a happy romance in Silence of the Lambs, how much do I really trust or believe the relationships presented in any other romantic comedy?

A recent video and film remix project produced by Paul Miller AKA DJ Spooky more fully explores the powerful effects, transformations and re-imaginings that remixing can achieve. Miller “remixed” the film Birth of a Nation, originally directed by D.W. Griffith in 1915. This film, which was the first feature length film produced and shown in the US, told the a general story of post-Civil War families. In 1915, the film was heavily criticized for blatant racism, violent mis-characterizations of African Americans and for idealizing and heroicizing the Ku Klux Klan - while many protested its release, others celebrated it, and this film became a point of contention that incited even more violence against oppressed people of color in the US at the time.

Referencing the current political climate of 2017, Miller decided to revive this project, entitled Rebirth of a Nation, which he originally began in 2004. Using remix as a conceptual principle in this work, as well as many of his other works, Miller talks about using remix and collage in order to both clarify and identify different systems of oppression operating within our society and culture, and also provide methods for dismantling them. Part of this deconstruction sometimes involves creating something else - a new narrative, or a new idea - but not always a fully realized “solution”. This type of work can be challenging to view - be sure to read through the article here in full, as it presents many of Miller’s intentions in his own words and offers important context, before watching the trailer.

7.4 YouTube

Before continuing with this lecture, please read this article about YouTube, and watch all of the videos included within it. This is a very insightful historical and contextual look at YouTube, written and produced by The Telegraph, that explains and contextualizes several aspects of YouTube. For this article, pay close attention to the “Education” section, and consider how YouTube has impacted art-making by streaming tutorials for different tools and processes that might be inaccessible otherwise, connecting back to the course theme of viewing the internet as its own “digital tool” / resource for contemporary artists.

Now that you have completed this article, absorb these facts from Mashable in 2011

More video content is uploaded to YouTube in a 60 day period than the three major U.S. television networks created in 60 years.

And then again in 2014:

In the one minute it takes you to read this text, 100 hours of video will be uploaded to YouTube. That's 250 days of video every hour, 16.4 years of video every day, and six millennia of video every year.

YouTube has essentially reversed the flow of video and media, which is something that has previously remained constant since the advent of motion pictures and television, even as services like iTunes, Netflix and Hulu were being developed. Prior to this, the majority of viewers were only able to access video via television networks, which were heavily mediated and only represented a tiny fraction of the video being captured worldwide. With the advent of YouTube, there was suddenly a centralized location to both contribute and watch video, which has continued to become more and more accessible to more users and viewers across the globe. In my opinion, this new order is far from perfect or in many ways ideal, however, it has caused undeniable artistic, social, cultural and political impacts that continue to resonate with every additional advancement.

As I have discussed before, photographs and videos partially construct and inform our real-world. Recall my anecdote about Muybridge and the horse, and how slow-motion videos of horses are the only way I “know” how a horse gallops, since it is something I cannot see that with my own eye. This phenomenon hopefully explains how YouTube has greatly impacted society and culture - we, as viewers, suddenly have billions of additional videos available to use to construct this meaning and our understandings of our world / reality. And now you will never look at Grumpy Cat the same way again.

Below are a few video works that interface directly with the YouTube platform as a digital tool and a resource for create artworks. They edit and recombine other user-generated YouTube videos in order to create brand new videos. This recombination is similar in principle to what the Dadaist were doing with collage all the way back in 1917 and (what other remix artists were doing in the previous chapter), with one major difference: instead of recombining well-known medias in order to challenge or redefine old meanings and produce new understandings, these videos expand and explore what might be considered “every day” content and re-frame it in ways that tell different, new stories. When viewing these videos, note your response. Do you find the original content more or less interesting after watching these? What new narratives, stories or ideas did you pick up on?

Below, sound and video collage artist Kutiman edits together completely new songs all from user generated content posted to YouTube. His final pieces work both as standalone audio tracks and video / audio collages. He has released two albums of this type of work, and credits each of the original videos he samples on his website.

Life in a Day 2011 directed by Kevin MacDonald is a feature length film compiled entirely of videos shot and uploaded to YouTube on July 24th, 2010. As you might have guessed, this film is available on YouTube in its entirety.

While the two are not directly related, when the 1 Second Everyday (1SE) was released, I immediately thought of Life in a Day - its kind of like the inverse method working with similar concepts. This app cuts together one second of video from each day of the year - it doesn’t access YouTube contributions, yet, but many of these compilations are posted on YouTube and I believe its only a matter of time before this starts to be integrated more with other social / streaming media platforms.

Streaming video platforms like YouTube are also undergoing a major evolution in this moment, as Live streaming becomes more and more prevalent and supported. This advancement brings with it a whole separate list of uses, as well as considerations and issues, which I will discuss in the next chapter.

7.5 Live (Life) Streaming Video

Live streaming video - broadcasting video live via data networks or internet connections to other social media or video streaming platforms - is a very recent technological development in terms of integration with existing platforms and accessibility for users without specialized equipment or setups. Facebook launched its Live Stream option in 2016, and YouTube recently followed suit by promoting its live, mobile broadcast option in 2017. These are the two “heavy hitters” in a live stream field that also includes Snapchat, Instagram, and Periscope. Each of these different applications offer slightly different features, but the concept is mostly the same - people can broadcast live video via just a smartphone with a data connection to a potential audience of hundreds or even thousands.

Different applications like YouTube and other streaming networks and platforms have been working with the concept of “live video” for many years. Webcams capture and broadcast live videos ranging from surf conditions to highway traffic to different animal dens and enclosures. A few years ago, my mom was obsessed with the live feed of a nest of owls, and all of the drama that ensued when the fledglings started flying and falling out of the nest. I will also admit that I have watched my fair share of wolf cams. And puppy cams.

The differences between these technologies and the most current technologies is that they were - and are - mostly one sided, and they required more extensive setups including dedicated hardware like cameras and cabled internet connections on the video capture end of things. The feeds were mostly passive, and viewers could not easily change, or interact, with the live-recorded subjects nor the video itself without a specialized program or installed application.

More recently, YouTube, Facebook and other live streaming networks such as Twitch have included ways for viewers to provide feedback which then becomes part of the live video content. This can be in the form of chat comments, audio, images, other live video and screen sharing. These options provide for more interesting user interactions, as well as more options for creating engaging video content. This technology is so new, that few artists are working with these platforms outside of very specific fields - but I believe there is a lot of potential to create compelling video-based artworks utilizing these new tools.

Below, screenshots from a Twitch Channel streaming a live play-through of a video game, along with the player's audio and video feed, and viewer submitted audio and chat texts (in the lower left-hand corner).

Accessible live streamed video is an incredibly powerful media with real-world social, cultural and political outcomes that have barely been assessed. In the year or so since Facebook Live launched, it has been used to broadcast and record multiple important events and occurrences, some of which are both disturbing and traumatic, but also important to disseminate. I believe that, as a society, we do not yet know quite what to do with this type of medium and tool. As an artist and just a regular media user, there is something very weird about using the same technology that can evidence protests or police brutality to also broadcast my brunch adventures.

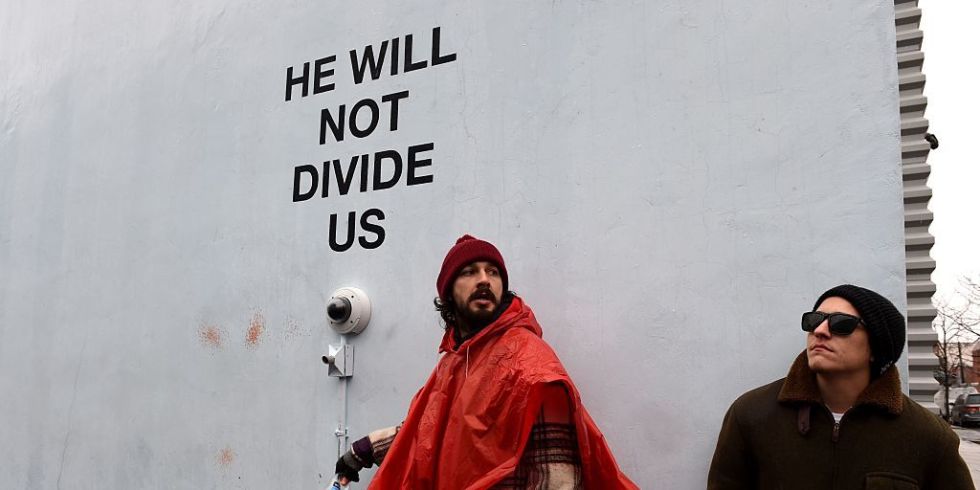

A recent artwork that attempted to grapple with unmediated, live broadcasted content illustrates many of these issues and challenges in working with live streaming video from a political or social context. Shia LeBoufs He Will Not Divide Us was installed during Trump’s inauguration weekend, and created a physical location for participants to repeat and or otherwise perform the phrase “he will not divide us” to the camera. These actions were also live streamed directly to the Museum for the Moving Image’s website, who curated the project, and a Facebook feed. In the end, the project failed in that multiple participants - including LeBouf - were arrested, and the physical site itself became a stand-off point for Trump supporters and opposers. The Museum of the Moving Image abandoned the project less than a month later, and it was fully shutdown on February 18th.

Mobile live streaming, for all of its complexities, has undeniable potential as a tool for artists working within social documentation, social practice, or any kind of activist art and work. Live streaming has already been utilized to broadcast several actual protests this year (as opposed to protest pieces) and this technology will continue to be explored and further integrated into these actions as time goes on. Please be sure to read this article addressing the many considerations at the heart of live streaming social actions and protests, especially if this is a digital tool you are interested in using to document or witness protests, political actions or other events. Video can be an incredibly powerful medium of resistance and revolution, but as the saying goes, with great power, comes great responsibility, and live streaming or filming the actions of protesters can have serious implications.

Above are two GIFs based on videos capturing a recent protest in Durham, North Carolina that were widely distributed and shared on Reddit, Facebook and then news media outlets. These videos document the unauthorized removal of a Confederate Soldier Memorial Statue by protestors 2 days following the tragic violence incited and enacted by hate-groups gathering in neighboring Charlottesville, Virginia, over the lawful removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. While I certainly consider these actions and videos important, powerful social practice art actions, the videos were also used by law enforcement to identify, arrest and charge the most active protesters with what many believe to be disproportionate, felony crimes. These events help explain why now, more than ever, video documentation and distribution is a complex, multi-faceted issue.

Below, a few more screenshots and stills from recent livestreamed protests and social actions, along with a pre-digital video captured and distrubted by a CNN camera crew in 1989. In the pre-digital era, journalists and photo/video-graphers were the first to be targeted and suppressed in protests and actions. How has digital technology changed the social activist landscape now that almost every person present can document and distribute images and video? What does it mean that some of this documentation is being used to identify and charge people?

A CNN crew covering the June 5, 1989, protests in Beijing recorded a man stopping a Chinese tank in Tiananmen Square - this was before digital technologies, but consider the impact that this video has had throughout the world.

7.6 Video Wrap-Up

So, I know this module has been a bit different from previous ones - I really want to stress that the above categories, videos and artworks are based solely on a few areas that I think are important to address with what is happening right now. The topics I present above do not fit any standard academic framework for talking about "Digital Video" or "Video Art", so, please don't think that to be a video artist, one is limited to re-creations, remixes and filming protests, or that video artists have only been active since 2008 with the advent of the iPhone. There is a huge body of work produced by video artists dating back to the 1960's and 1970's - to check out some examples of more commonly classified "Video Artworks", see Chip Lorde's expansive library of video artworks , or works by Bill Viola and Pipilotti Rist. These artworks and artists exist more within a gallery-based definition and system of video art, with the exception of Chip Lorde's groundbreaking Ant Farm and other media-based artworks, which focused on dismantling and creating art outside of these systems.

As for the works shown in this module - I wanted to provide possible entry points for people in this class, and also offer context for the video media a lot of us consume on a daily basis. For each of these categories and mediums, keep in mind that they are all either incredibly new, or deal with technologies that are constantly advancing or in flux. This means that while there might be less pre-established ways to utilize this technology to create and distribute artworks, there are also less boundaries and expectations. I believe this is a moment in time that artists need to be expanding the use for these technologies in ways that haven’t yet been imagined - and I encourage each of you to recognize the artist, designer, filmmaker, innovator, engineer, radical, scientist, activist and/or creator within to take these tools and apply them in whatever direction or field that means the most to you.