ARTG 91 - LECTURE MODULE 1: CONCEPT ARTWORK

LEcture Module 1 - Concept Artwork

This Lecture Module will focus on different strategies and methods for first developing a game’s overall look and feel, along with creating sketches of potential characters and environments, which will be further discussed in Lecture Module 2. This ideation and conceptual visualization is an integral part of any game’s art production, regardless of format, scope and the size of your production team. Even if you are working on a solo project, it is important to fully develop potential ideas and directions by experimenting and researching visuals in order to better define the tone, feel and focus of the game. As we will discuss throughout this module, this type of development and exploration can be done via mood boards, collages and quicker sketches, along with more developed drawings and artwork. In developing concept art, you can turn intangible ideas into something visual and also work to create the most successful art direction and visual focus (which includes constraints) for your game.

As you will see in the examples presented in this module, concept sketches and artwork can start as very simple sketches, and then evolve into more highly complex and refined drawings or visuals. It can be art that is shared only with the production team, or ones that are presented to a larger audience as promotion or previews. In many cases, concept artwork and sketches are distributed even after a game ships, and can often add another layer of depth to a game’s overall tone and style, depending upon how they are utilized.

In the Studio Module, we will also use concept sketches and concept artwork as a springboard for working with Adobe Photoshop, a pixel-based image editor. This will be covered and discussed primarily in the exercise tutorial videos. By the end of this Lecture Module, we hope to present a few different ways that game artists utilize concept sketches in order to explore a game’s visual potential and also define a game’s overall style, mood and art direction. The Studio Module exercises will demonstrate how a program like Photoshop can be used to develop this concept artwork and utilize pixel-based processes and the program’s affordances to better explore visual elements such as color, texture and atmosphere or style.

A Brief Timeline of Early Concept Sketches and Artwork in Games

Game developers have worked with initial sketches in some form or another since the advent of digital games. Early text-based games are visual - letters and words are visual symbols, and take on a visual form. These types of games also integrated visual layouts, interface and/or control elements, all of which needed to be designed, where it was possible technologically. Primitive ASCII Dungeon crawlers built entire environments out of textual characters and symbols, and these worlds needed to be planned and sketched out before implementation.

Even the earliest fully graphical games - think Pong - required many intentional visual decisions to be made. Yes, these early game visuals were also highly dictated by technological constraints in terms of processing power and display output. Many visuals were sketched out directly on graph paper with a monochrome or highly limited color scheme, but there were still design choices and ideas to explore. Things like component scale + proportion, location within the screen, player control components or player characters and game world elements and boundaries all needed to be seen and experimented with “on paper” before attempting to program into a game.

As technology began to advance in the late 1980s, concept designs were able to be more complex. Note how the designs below are more descriptive than the graphics above, but still have to consider output and graphic limitations of the time.

Beyond Concept - Building Worlds + Universes

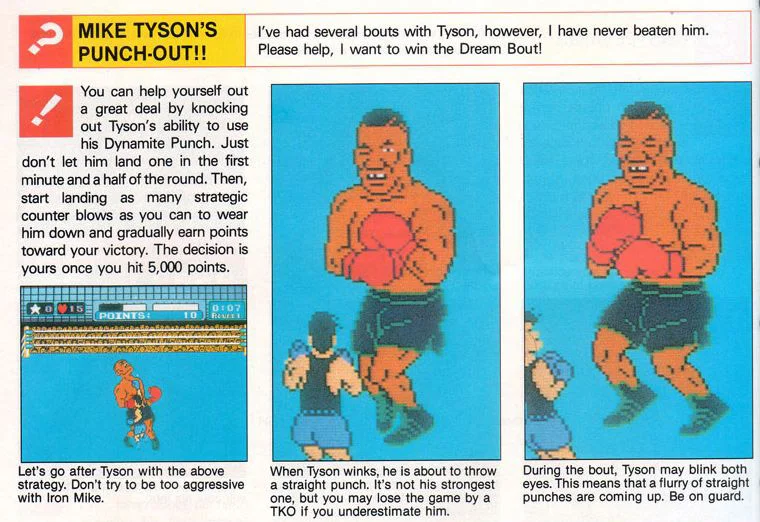

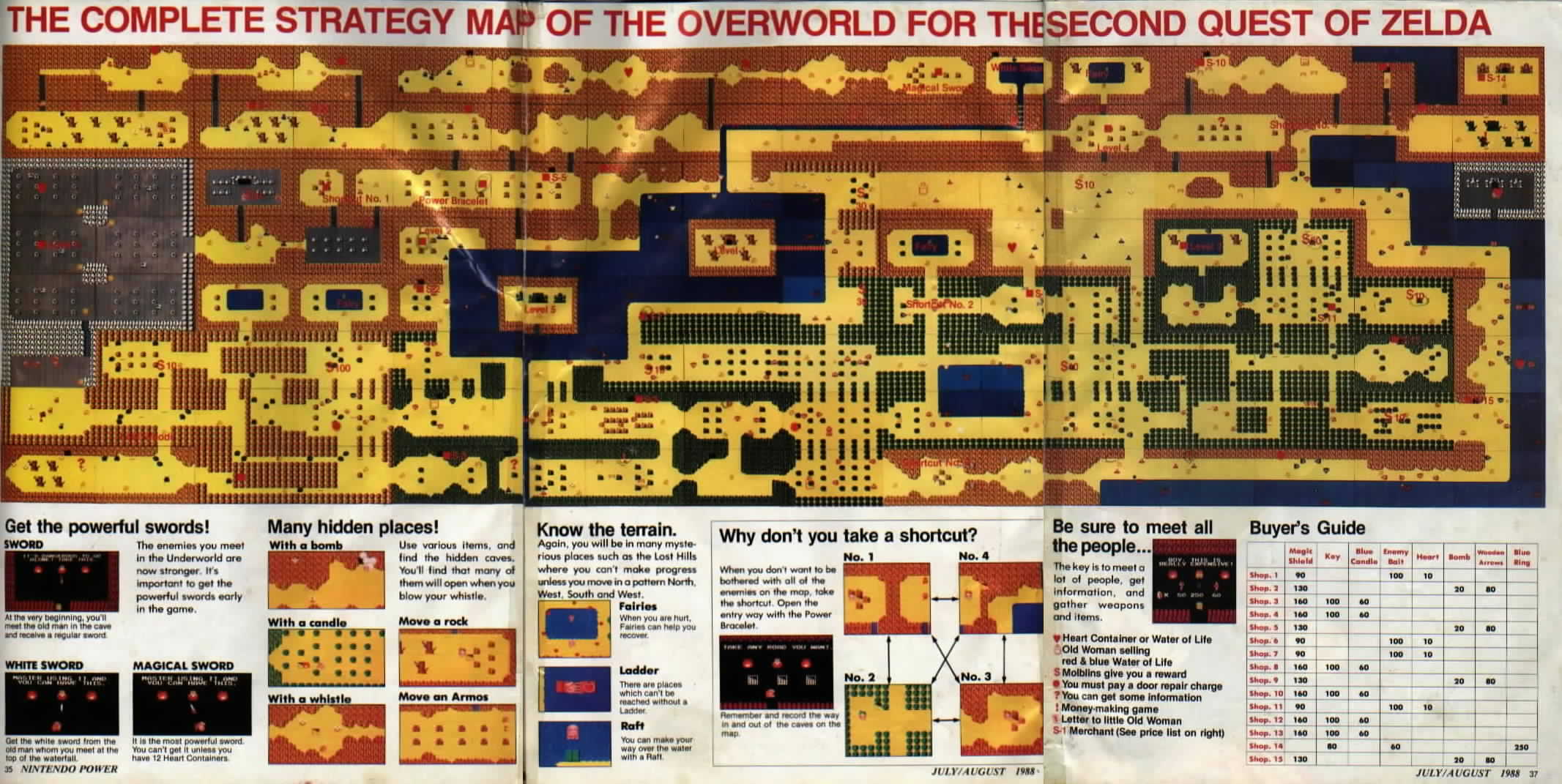

Due to technological limitations, early games concept sketches and other explorative artwork were extensively more visually captivating, engaging and expressive than the in-game graphics could be. For these reasons, sketches were often further developed into refined concept artwork and other communication or promo materials for things like packaging and advertisements. Look at the examples below of these images compared to the in-game graphics of the corresponding games, and try to imagine how these visuals might have added layers and depth to the actual gameplay or game-worlds in the player’s head. This type of world-building is a very interesting strategy that I believe added depth to most early games - the literature (both in terms of visuals and other narratives) surrounding the games was something that the player absorbed as much as the graphics, and this “informed” or expanded that game world in the imagination.

One company and game production team that was incredibly smart with this strategy was Nintendo, with their magazine Nintendo Power. This publication - which people paid for - covered games and devices designed by Nintendo and other partnering developers. Each feature included pages of rich concept artwork and images, along with a few in-game maps and screenshots to provide a bit of context, and truly worked to expand the game world without ever being a part of the actual game or gameplay itself. From this perspective, Nintendo Power was able to advertise new games to players and expand their audience, but also continue to craft a visual mythology for players after they had purchased and played a game.

This, of course, is no longer always the case for contemporary games - often times, in-game visuals are as detailed, vibrant and engaging as any concept artworks, and, unlike concept stills, can also include animation and time-based effects. Even with this shift, there are many modern games that build worlds that are partially constructed, informed or even enhanced (in the player’s imagination) by things like concept artwork and other out-of-game visuals and objects, from packaging, to version extras and swag, to fan-generated art to printed art books. Keep in mind that these types of materials are a different part of the art production process than concept sketches, but they can absolutely be derived from them, just as they were in the earlier examples above. This type of world-expansion using concept artwork is also not limited to just digital games - films, table-top and card-based games, albums, comics and many other types of media also use concept artwork to expand their visual universes and promote their core artworks.

When viewing these more recent examples, think about the types of concept materials that you have noticed different game developers using to promote upcoming games. This could range from Indie Developers utilizing concept artbooks as incentives for a Kickstarter campaign, or AAA Developers promoting games with Collector’s Editions. Have you come across any particularly successful or effective uses of these types of materials in the past few years?

Contemporary Concept Mapping, Concept Sketches and Visual Development

All of these examples demonstrate the power of concept artwork, along with its importance in the initial stages of game art production. Now that technology has in many ways caught up with our imaginations and ideas, and it is possible to produce in-game visuals that are on-par with (or could possibly surpass) what we might see in our mind’s eye, starting with concept sketches is even more important to the game design process. Without technological constraints, there are limitless possibilities, so, organizing and shaping these possibilities is incredibly vital to creating a focused, visually successful game with a cohesive art direction.

Below are some specific examples of how mapping, sketches and other visual explorations are integrated in the game art production pipeline, and outline some of the main focuses of initial concept exploration.

1. Mood - Color, Texture, Atmosphere

When planning out a game world, these are some of the first elements to consider and organize. In most cases, the mood or style of a game can define the specifics of all other components of the game world. These elements - things like color, style and atmosphere, represent the building blocks of a game, and are usually developed in connection to the game’s “story”. This story can be a specific, pre-existing narrative that the original game idea is based on, or, it can be a narrative that is developed as part of the game’s original inception.

These types of attributes, core elements of the games overreaching style or theme, can be applied to many different genres and game formats. For example, imagine a the artwork for a zombie game - what do the zombie characters look like. Now, imagine the same zombie characters based on the following descriptions:

Animated Zombie Adventure with Toon-Based Hi-Jinks - Find and Organize Your Undead Friends + Family Before the Pesky Living Eradicate Them For Good

Zombie-Noir Detective Puzzler - Navigate a World In Limbo to Find Your Multiple Killers Before Time Runs Out and You Forget Who You Were….and How To Get Back

These descriptions most likely change key aspects of the character you envisioned, as well as the game world as a whole. With a few words, they add details to the visual world of these imagined games, and help define a clear style or starting point, regardless of the expectations a format or subject might originally outline. These short descriptions also help define what WONT be included in the game’s visual style. This type of mood exploration is, therefore, a critical part of a game’s initial art production, as it helps define a games visual art direction.

Below are a few different examples of moodboards focusing on the same subject, but working with different organizations and selections of images. Looking at these example, think about how different colors, textures and imagery can evoke very different emotions and meaning.

Developing mood boards can be a first step in defining the overall atmosphere of a game. These can be collages of colors, textures and photographs that relate more to a feeling than a specific character or environment. Seeing these images together in one space can be a quick way to help explore and test out different possible directions a game might take. As you explore different potential moods and imagery, you can begin to craft out a more focused or cohesive style or theme. This also begins to introduce the idea of constraint, which is incredibly important in contemporary games: since visuals and effects are no longer as limited as they once were by technological factors, you must impose your own set of constraints. When defining constraints, I find it useful to think about them not as hard boundaries to where you can’t go, rather, they are the pathways used to navigate through a larger possibility space.

2. Reference, Inspiration + Style

Once you have begun to implement a visual style or mood to a game, you can begin to further explore this mood. This could be considered the research or reference phase of concept art development, where artists look at reference images or inspiration images to help define elements of a game’s atmosphere, and begin to narrow down more specific elements to be utilized later on in the production process, such as with characters or in-game environments. We will discuss specific ideation and research phase strategies for character and environment concept art development in Lecture Module 2. For this module, I will focus more on things like reference images, styles and inspiration images that instead inform the games look and feel - these can be any type of materials that influence a game’s overall art direction or style, also referred to as its aesthetic.

Below are a few examples of recent games and the inspiration materials they utilized within the research phase to inform their games’ overall aesthetic. These reference materials includes other types of visual media such as paintings, photographs, illustrations, print design and film, written media such as stories and poems and sound and audio such as lyrics, music or even musical styles. In each of these cases, these materials were crucial parts of the concept art production process, and help construct the general mood, color and overall atmosphere of a game.

I have found that one pitfall of this type of process is when developers and artists rely too heavily on other games, game genres or game formats to inspire their game. While considering format and genre, and understanding these types of conventions is hugely important, if you are only building visuals based on another game or set of games, it can severely limit a game’s uniqueness and also creates a very narrow set of artificial constraints to work within. Additionally, while you might be working with the same format as another game, the narrative or story driving the two games might be completely different, and this is where pulling from inspiration material outside of the gaming world is incredibly important.

In the next lecture module, we will look closely at the concept art phase of character and environment development in games. While we are looking at these different aspects of concept art and art production at different times in the course, I want to stress that these phases are not completely linear or contained - even in the conceptual exploration phase, initial character and environment development are often happening at the same time, and often times these components all intersect and inform one another. In many cases, the characters or settings of a game are connected to its overall style, or, alternatively, might dictate some sets of constraints or a specific direction. It is important, however, to generally work from big to small, or to think of the conceptual art and ideation phase as an umbrella that covers things like character design and environment design. There might be overlap and back and forth between different game components during this exploratory phase, but generally, this foundation must be present before moving on to any kind of “in-game” assets.

Looking Outside - A Note on Retro-Styles

One interesting and relatively recent trend that is important to discuss in this module is the use of art styles that are informed by older game art. These styles were originally dictated by the limits of older technological constraints and output technology. Metroidvania games or rogue-like dungeon crawlers that utilize pixel art graphics or tile sets are perfect examples of this type of inspiration style. Contemporary games that work with this type of defining style can have very powerful visuals and do evoke a certain mood, not to mention nostalgia, but it is still important to work with outside reference and inspiration materials in these situations, and not just pull directly from older games.

Another compelling use of this type of inspiration and style is when the constraints are used selectively and combined with more advanced visual output and game effects. This technique can be observed in the combination of 8-bit graphics and rich gradients and animation effects in games like Hyper Light Drifter, #Sworcery, and Gris, or in how The Return of the Obra Dinn applies a black and white bitmapped style to 3D environments and animation.

Case Studies

Watch through the 2 GDC presentations below to have a better understanding of a few ways that developers work with art direction and overall art development for games. Consider the different outcomes that result from working with traditional and non-traditional art direction from the beginning of a game dev process versus deciding on an artistic style much farther into a games development.