ARTG 91 - LECTURE MODULE 2: CHARACTERS + ENVIRONMENTS

LEcture Module 2 CHARACTERS + ENVIRONMENTS

1. Intro

This week in lecture we will focus on 2 different aspects of game art production - the development and creation of character and environment assets in games.

Last module, we looked at how concept art can be used to define a game’s overall look and feel. This is an initial development phase, usually happening at the same time that a game’s format, core mechanics, story and other foundational design components are determined. Conceptual art development also plays a crucial role in the ultimate production of in-game assets like characters and environments, and these components also include a conceptual phase. In this module, we will focus on some possible strategies and methods for conceptualizing game characters and environments. We will also discuss how game artists go from concept sketches to in-game assets, and observe a few real-world case studies that go into this process more in-depth.

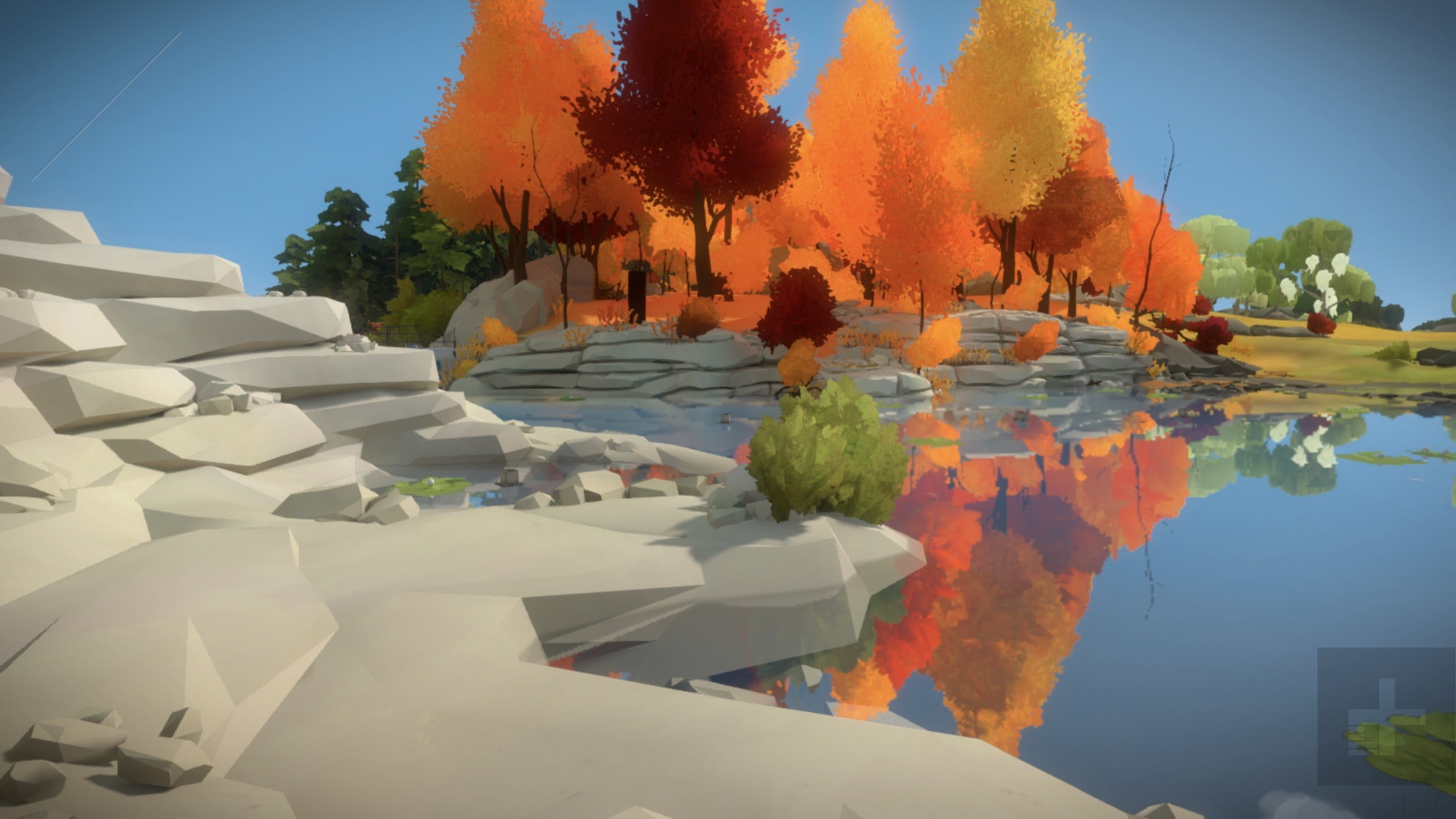

Since this is an introductory course and we are working primarily with 2D production, many of the finished examples I list in the module galleries focus more on 2D characters and environments. This is because these examples might be a bit more attainable when it comes to applying similar techniques to your own projects for this course. This is not to say that working in 2D is easier - I think 2D formats actually require artists and designers to be more effective, as they are trying to communicate the same amount of visual meaning and information with much less bandwidth. Working in 3D also adds a few layers of technical complexity that can be difficult to separate from art production, and sometimes this format is tied to achieving a sense of “realism” over a unique game world. When choosing 3D or 2D/3D hybrid games to focus on for this course, I try to select games that I believe work within the 3D format to create uniquely styled, immersive worlds (such as Fortnite, Journey and Kentucky Route Zero this week) instead of ones that are more concerned with producing highly believable worlds that match our own.

2. Character Development, Design + Art

Conceptual character design is similar in method to visualizing a game’s overall mood, tone and art direction. It is very typical to begin with a series of mood boards and/or sketches to slowly narrow down character possibilities into manageable categories. Often times, this funnel approach can start with a wide spectrum of options with basic constraints applied, and slowly narrow down that original list. Once a particular character category is more defined, they can be more fully explored in the next phase, the research phase, where more detailed characteristics can begin to be applied and tested.

An example of this process is illustrated in the conceptual progression below. One of the character types in the game is a land-based, protective, animal-like creature - these are design-based aspects that are dictated by the game’s story and mechanics, also introducing constraints. After creating mood boards with 3 different options to consider that fit these general constraints - bears, cougars or elk - the bear option is chosen by the development team.

Once this character category has been more defined, more detailed characteristics are brainstormed in the research phase. In this example, different visual options for the bear character are explored to see which set of attributes fit best within the gameplay, narrative and overall tone and style. If a game’s aesthetic is dark and foreboding, a grizzly bear might make a better reference image to start from than a koala bear or panda bear cub. If the game is set in a snowy environment, a polar bear might fit that narrative best. If the bear character is supposed to slide smoothly on its back through ice caverns, the physical design might focus on very different features than if its meant to stand guard in front of a cave. This is when quick, gestural drawings can begin to be utilized to test these different physical aspects.

The final phase of this conceptual character development involves experimenting with different textures, colors and dressing applied to the more defined character form. In this example, these specifics can include exact fur coloring (black, brown, blue, polka dots), textures (smooth coat, bushy coat, puffy coat), and dressings or any associated objects (armor, hats, clubs, banjos). These details mark the transition to a more iterative design phase, where some of these different options are explored further in concept drawings while others might need to wait until working with actual in-game asset designs and play-testing them.

When thinking about these details, there should be some reasoning behind each decision that relates to narrative, gameplay, overall aesthetic or the larger game world. Outside of the specific bear example above, there are many game play mechanic and narrative considerations that could - and often times should - impact the visual appearance and design of a given character. Below are a few of these factors explained more in-depth.

Core Gameplay Mechanics / Functionality

Sometimes core gameplay mechanics might factor into a character’s visual appearance. If flight is crucial to gameplay, then your character might need to have wings or a tool / appendage that enables flight (such as a propeller beanie or a raccoon tail). If navigating through different sized tunnels, doorways or mazes is a core navigation mechanic, then the character’s visual size or scale might be very important to define. Changes to character shapes or sizes can often reflect changes in abilities or mechanics. If these types of visual features indicate critical abilities or gameplay mechanics, they are often exaggerated or otherwise highlighted in the character design.

Other more superficial visual properties, such as coloring, material / texture, clothing, facial features, hair + fur, accessories (like shoes or backpacks), can also bring the player’s attention to a characters specific abilities, state changes, or unique functions. This can be something like brightly colored fur or clothing that attracts the player’s attention to a part of the character.

The examples below range from classic to contemporary games. Different visual properties such as color, texture, dress and accessories, along with basic character construction, communicate information about that character - and their role in the game world.

Below are character designs from the Don’t Starve series - note how relatively minor superficial differences in facial features, dress and accessories communicate about possible abilities and other character traits using purely visual information.

Character Differentiation / Contrast / Relationships

If there are many different characters in a game, then it can be important to create visual contrast between different types, such as player characters, non-player cooperative characters, “enemy” characters and neutral characters. Outside of actions and behaviors, scale, color, shapes, clothing and/or accessories are often used to help differentiate different categories of players, and sometimes indicate relationships - NPCs with similar scale, clothing and/or styling to the player character(s) usually indicate they are helpful. NPCs that are significantly larger in scale to player characters often indicate some kind of threat, like an enemy boss character. Large numbers of NPCs with very little visual variation among one another usually indicate that they are enemy or obstacle characters that are less integral to progression.

In most games it is especially important to differentiate between vital and non-vital characters, and other environment elements and assets. This can be done through different visual features like accessories, colors + textures, contrast among environments and other characters, or level of detail. Generally speaking, the more detailed a character, the more important they are to the gameplay and/or narrative. In most cases, background characters should never be more detailed than player characters or other important non-player characters.

Below are screenshots of Hollow Knight (top) and Axiom Verge (Bottom). A major criticism of Axiom Verge has been that the player characters and enemy NPCs are very difficult to separate from other non-essential characters and envrioment elements. Hollow Knight, on the other hand, demonstrates excellent contrast between environments and characters, one that also balances out the games main thematic elements of darker, atmospheric locations and content joined with more animated motion and mechanics. Many reviewers find this visual combination to be a rewarding game play experience.

Wrapping Up - Editing, Refining + Player Customization

Editing character designs - especially in 2D games - is crucial to the art production process. As discussed above, a character’s visual output should indicate important narrative details, core mechanic functions, state changes and/or special abilities, indicate relationships between characters and/or distinguish between different characters or different character sets. This can leave little bandwidth to include extra features or details that don’t play into the game or story in any other way. The visual affordances of Third-Person games like Fortnite, Zelda - Wind Walker + Dark Souls 3 allow a bit more “visual room” for players to customize and stylize their characters, often times with different superficial items, clothing or full character “skins” that are earned via quests or achievements. In these situations, the template characters are produced by character artists in ways that can accommodate many different options, but still maintain core visual components or markers for basic identification (when necessary).

Case Study - The hand-drawn style of “if found” and it relation to game mechanics and narrative

Below are a series of images and the trailer for the recent game If Found released by Dreamfeel. The story {and gameplay} revolves almost primarily around a sktechbook / journal, and the game exhibits a highly hand-drawn and illustrative feel that is rare among digital games. Read through the short articles linked below, and consider how these visuals relate to the content and story of the game - these types of connections will be explored more in future modules.

If Found’s style is somewhat similar to the artwork and graphics in the game Florence. The article below is an insightful look at how the developers and artists at Mountains approached creating and illustrating characters for the story-driven game Florence. This article is optional for this course, because the lead artist interviewed in this article, Ken Wong, has recently been publicly named as a perpetrator of workplace aggression and verbal abuse by Florence co-developer Tony Coculuzzi. Wong issued an apology, however, I did not want to make this required viewing/reading for anyone in the class. As a gamer, artist and designer, as well as an academic, this is a conflicting aspect of looking at industry examples, because the end products are the result of so many people’s creative labor (unlike, for example, a painting or a sculpture made by one artist). It is complicated to essentially censor or exclude that labor and the collaborative result due to one person’s actions, however, I think it is important to note it, especially as folks are considering future employment in the industry and to honor the experiences of those speaking out.

Case StudY - SUPERHOT - DESIGNING A UNIQUE FPS

The video linked below is a 2016 GDC presentation by Superhot Designer Piotr Iwanicki. In this video, Iwanicki describes how the overall gameplay design goals, and the experience they wished to craft for players, greatly influenced the character and environment designs for the game. This example is especially interesting because the visual aesthetic of the game is very unconventional for the First Person Shooter {FPS} format. Consider the link between the formal designs and Superhot’s unconventional gameplay.

Watch the presentation, up until the Q + A, which is optional. Link below must be used, there is not a YouTube version of this talk. No quiz questions are based on this video, but it is required viewing for the lecture content. Video presentation and trailer {embedded below} contain animated violence, including some animated gun violence. If concerned, skip minute 0:00 to 1:30 minute and 6:30 minute to 8:30 minute of the video presentation.

https://www.gdcvault.com/play/1023483/Game-Design-and-Mind-Control

3. BUILDING ENVIRONMENTS + WORLDS

In terms of sheer area and scale, environments are - literally and figuratively - a huge part of any game world and player experience. Even if you are developing a game rich with characters, the environment usually dictates the game’s possibility space, defines where the player and other game characters can navigate, and often times imposes much of the gameplay constraints. There are also many types of games - like puzzle games or rhythm games - which completely lack traditional characters, and the environment and/or environmental components are the main point of player interaction and gameplay mechanics.

Because environments are such integral aspects of a game’s visual composition and core mechanics, it is very important to go through a conceptual design process and planning phase with them as well. When conceptualizing environments, there are the visual aspects to consider as well as the boundaries and constraints the environments need to set for the gameplay mechanics.

Since environments and environment features are such a key component of gameplay mechanics, and also dictated by the game format, they will typically be built out as in-game assets sooner in the development process than character assets might be. Often times, an environmental feature’s visual and stylistic details will be explored and assigned after the basic form has been integrated into the game’s testing system. This type of process is called “grey-boxing”, and it is especially useful in 2D or isometric games that utilize tile sets where features are a very specific set of sizes, and entire levels or areas can be built out in placeholders. For 3D games, less detailed placeholder models - with very little texture or color details - are usually first utilized to block out maps and/or levels.

From a conceptual visual standpoint, environment artists need to experiment and define things like game-worlds (fantastic moon-scape, magical elf mountain) and more specific settings / locations (an ancient city, a secret forest) based on the narrative and gameplay mechanics. Once these visuals are organized, artists then start to work with more specific features - such as trees, walkways, roads or buildings - that the charters and/or the players will be interacting with or navigating around / through. These features need to tie into the visual world the artist is creating, and also function as part of a convincing constraint system.

Environment artists need to be concerned with both the functional side of the environments, as well as the visual side - this visual quality is sometimes called the “formal” side (in relation to visual form, not formal like a tuxedo). Below are some of the main considerations that come up when developing and then building out environments in the game production process. I have tried to group these into mostly functional considerations (things that determine and/or are dictated by gameplay mechanics), and mostly formal or visual considerations (things that are more tied to the tone / style of the game, and in some cases, the game narrative). Keep in mind that these are not distinct categories, and that there is a lot of overlap and influence between functional and formal components in most game environments.

Functional Considerations

Game Format

A game’s intended format / perspective - such as platformer, top-down, isometric, first-person, third-person etc defines the core CONSTRUCTION of most in-game environments. The most basic concept work can be done with mood boards and environments before determining this format, however, format should be implemented into visual development very early in the process. This is because this construction is going to heavily influence many visual aspects of environments, and it is important to only be experimenting with environment characteristics and ideas that are possible within format constraints. For example, if you are creating environments for a top-down 2D shooter, you don’t want to be exploring 3D-modeled landscapes and features.

Below are a variety of the different game format iterations that Legend of Zelda games have utilized over the past 35 years. When envisioning environment art for each of these games, the game format heavily dictate not only how the environments can be built and their visual limitations / affordances, but also impact how they might function within the game and what purposes they serve.

Constraint / Navigation System

How does the player navigate through or interact with the game world / environment, and how does the environment impose boundaries on and direct that participation? Environment assets often tell the player where they can and cannot go and/or what they can and cannot do. These constraints are often inextricably linked with things like format and gameplay mechanics - environments help the player learn how to operate within the game world. They define what type of navigation / movement or interaction is always possible (moving back or forth along a path), what could be possible (jumping from one tree branch to another, unlocking a door, pushing blocks together), and what is impossible (running across an ocean, morphing through walls, exploring off the map). Environments can often times be thought of a series of visual navigation rules a game. This is especially true for puzzle games, where environments dictate all gameplay mechanics and progression.

Environments work within the game world to visually spell out these boundaries, in ways that make sense - or are intuitive - to players. For example, things like fires, spikes and bottomless pits make sense as dangerous obstacles because of their visual meaning, while a pathway indicates safe navigation. Puzzle games build player understanding by introducing them to the system of the world - often times these components work together in ways that make sense visually and employ some sense of physics or real-like functionality, or are different sets of rules are quickly learned. If, suddenly, the game broke away from these systems and began behaving different, it could lead to a very negative player experience. Once any environment’s visual system has been established, whether it is defining navigation or interaction, it is very important to maintain that system throughout the game.

Scale

This consideration is both formal and functional. A game’s environments need to fit the scale of its core mechanics - a platformer needs to work with features that are navigable by player characters, top-down shooters need to work with a landscape that is zoomed out enough to see what is coming but not so zoomed out that all enemy formations or obstacles are immediately in view. From a purely visual standpoint, you want the scale and/perspective between environments, features and other in-game assets to make sense, unless there is a specific narrative and/or mechanic reason for this not to be the case.

Formal / Tonal / Visual Considerations

Narrative elements

When working with games based on specific narratives, these story-based details and the corresponding visual characteristics are very important part of environment visuals. This includes games or gameplay that are based on historical or fictional events, game worlds based on specific locations / settings, both real or imagined, and games working within a specific fictional universe or time period. Some game environments are highly informed by these types of narrative components, while others might be working with a less specific or well-known narrative.

Feature material, texture, color + other details

These types of visual qualities create a strong sense of meaning, but are less crucial to the overall functionality of an environment. These decisions are often heavily linked to the games overall tone and style, as defined in the concept phase. For example, if walls are going to limit navigation and create boundaries in a top down RPG, the function is clearly defined, but there are many ways to color, texturize and otherwise visually construct these walls, which will be decided in the visual art direction phase. Will they be made of stone, metal or wood? Will they be a natural or material color, or will they be painted? Will they be covered in spikes, or metal sheets, or vines? How will they be differentiated from other features, such as pathways or doorways. Will there be different kinds of walls on different levels? If some walls are able to be destroyed, and others are indestructible, how is this visually noted for the player?

Below are examples of different environments in the farming sim Stardew Valley. After defining the environment possibility space - including the range of different land, water, soil and vegetation types, building materials and other environment features, what kind of navigation, planting, cultivating and building could happen on different types of land and soil, and what those actions required, the artist also had to define the building blocks of these features. How would soil and rock land types be distinguishable? How would different crops and farm buildings still look unique, but like they were from the same game? This is defined through style, color palettes and consistency of small details, like flowers, leaves and patterns in building materials. These small details are incredibly important for creating consistent, immersive worlds, but they can also be refined much farther into the development phase.

When working with more open-world environments, these types of details are explored and defined in an extensive research phase. This is especially true when working with fictional worlds and settings, where the smallest types of building blocks - such as crafting, building and manufacturing materials, or plant and vegetation species - need to be classified and drawn out in order to create a cohesive and convincing environment. If a fictional game world features buildings and cities made almost completely out of planks of pink timber, then the surrounding forests should probably not consist of only blue trees.

Below, the screenshots from Shadow of the Colossus demonstrate how the monster characters are heavily informed by the surrounding environments, and fit the tone, color, texture, material and even architecture of those environments. This creates a convincing world with powerful visuals that makes sense to viewers, even though it is not “realistic” (in that we don’t currently live in a world where giant monster-like creatures emerge from canyons and mountains…) This is also why I believe this game is so engrossing to play in a dark room.

Generally speaking, the more important the feature, the higher level of detail should be applied - this can help develop a hierarchy for the player’s attention and focus, and also help organize the development process of in-game assets. It can also help the player know which environment features might be crucial to in-game progression - this is another example of how these visual aspects can overlap with and influence gameplay and mechanics.

Atmosphere, Light / Shadow + Time (of day)

These types environment characteristics usually overlap with some type of gameplay mechanic, especially if the game environment features changes in time, weather and/or illumination. If this is not a part of a mechanic, however, it can still heavily influence an environment’s look and feel. How dark or light is the environment? What time of day is the gameplay happening in? Is the environment bright, with high visibility, or is the environment, with areas of fog or shadow obscuring some parts from view.

The game below, Gardens Between, uses fog and light to constrain character navigation. Players also control time and order of events within the environment, instead of directly controlling a character’s movement or actions.

CASE STUDY - From Concept to Asset - Supergiant Games and Hades

A critical point in the game art production process is when characters and environments make the shift from concept drawing to in-game asset. The video below looks at how Supergiant Games went from concepts to assets for their 2019 game Hades. This video documents how both visual and audio assets are experimented with, tested and revised over multiple rounds that include a lot of visual play-testing. There is no one set formula or program for building out an in-game asset, but I think it is useful to hear and read about how different artists and teams work, especially on game like Hades with compelling and engaging aesthetic aspects.

While the entire video is super interesting and recommended to watch the whole thing, it is only required to watch from 8:30 minutes to 21 minutes, because this is where they discuss the visual assets. One quiz question is based on this video.

Case Study - Developing Kentucky Route Zero’s Environments

The video below describes the creative process that generated Kentucky Route’s Zero’s environments. While these environments certainly impose constraint and gameplay boundaries, and dictate KRZ’s core exploration and puzzle-solving mechanic, they are also key narrative components, and work to slowly tell a story as the player progresses through the game. This is a key aspect of most adventure games. As you watch this video, think about the all of the outside influences and reference materials the artists worked with to create these environments. How did film and cinema inform the way these environments were presented to - and navigated by - the player?

Watch the entire video - No Quiz Questions are based on the video, but it is required for the lecture content.

Case Study - Cruelty Squad + Visual World Building

Below is a Vice article detailing the design process and thinking behind 2021’s indie genre-challenging game Cruelty Squad. This game features a very unique set of character designs and a game world that is inspired by 1990’s PC game graphics, glitches, and general technological…weirdness + subversion. I believe this game presents an opportunity to consider how much visual aesthetics can influence the experience of a game, and even the gameplay itself, where it cannot be separated from mechanics {rules, action, player and NPC behaviors, interactions, controls, etc}.

Article is required, videos embedded within the article are optional {see warning below}. No quiz questions are based on this article.

Important Audio / Video Content Warning - there are a few videos of gameplay linked within this article. The game itself contains flashing lights, fast animation, visual and audio effects such as strobe effects and disruptive sound, and just a lot of very disorientating visuals. Folks with audio / video sensitivities should be proceed with caution. All videos are completely optional.

Case Study - From concept to game - Fortnite

The Game Developer’s Conference (GDC) video below, features the story behind Fortnite’s Thematic + stylistic development. This video is a great case study that demonstrates the importance of conceptual exploration and iterative art direction, not to mention the feedback and review process, and how this will inform both character designs and environment designs. Fortnite was originally envisioned as a dark, noir-like urban zombie shooter. It also shows how crucial concept art is to the game art production process, and how a game’s overall art direction hugely impacts the overall player-experience.

Recommended to watch up until ~44:00, especially starting at 11:00 minutes. No quiz questions are based on this video, and it is optional.