MODULE 1: FRAME ANIMATION + ROTOSCOPING

INTRODUCTION

This week we will be looking at how different artists have created what are considered "frame" animations from roughly the past 200 years, with a few examples that date back 30,000 years or so. We will be viewing many early animation examples as well as early film examples, as a way to understand some different animation principles, and to also understand how different types of animation and animation techniques have evolved with the advancement of different technologies.

I will be introducing a few different sub-categories of frame animations, and then showing a range of artworks that fall within each of these categories. While these are standard ways of classifying different animation styles and techniques, there is always overlap between categories, and there are also terms that can describe slightly different things depending on which type of animation process is being used. I will try to clarify when these discrepancies come up.

106-O Student Projects - Frame Animation + Rotoscoping

By Anna Leon

By Lisa Durand

by Thovatey Tep

Frame Animation Tutorial

Enter Animation

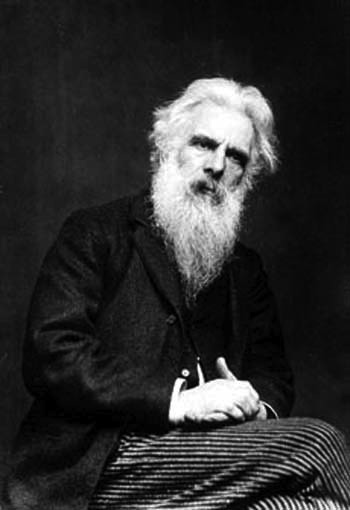

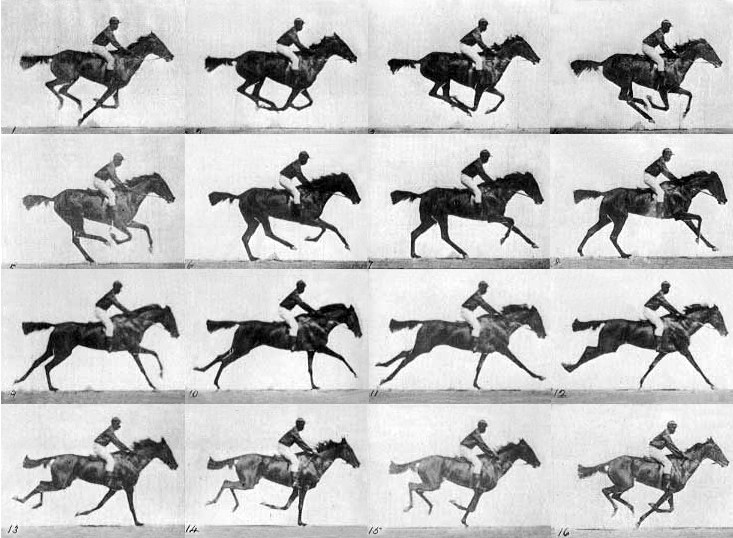

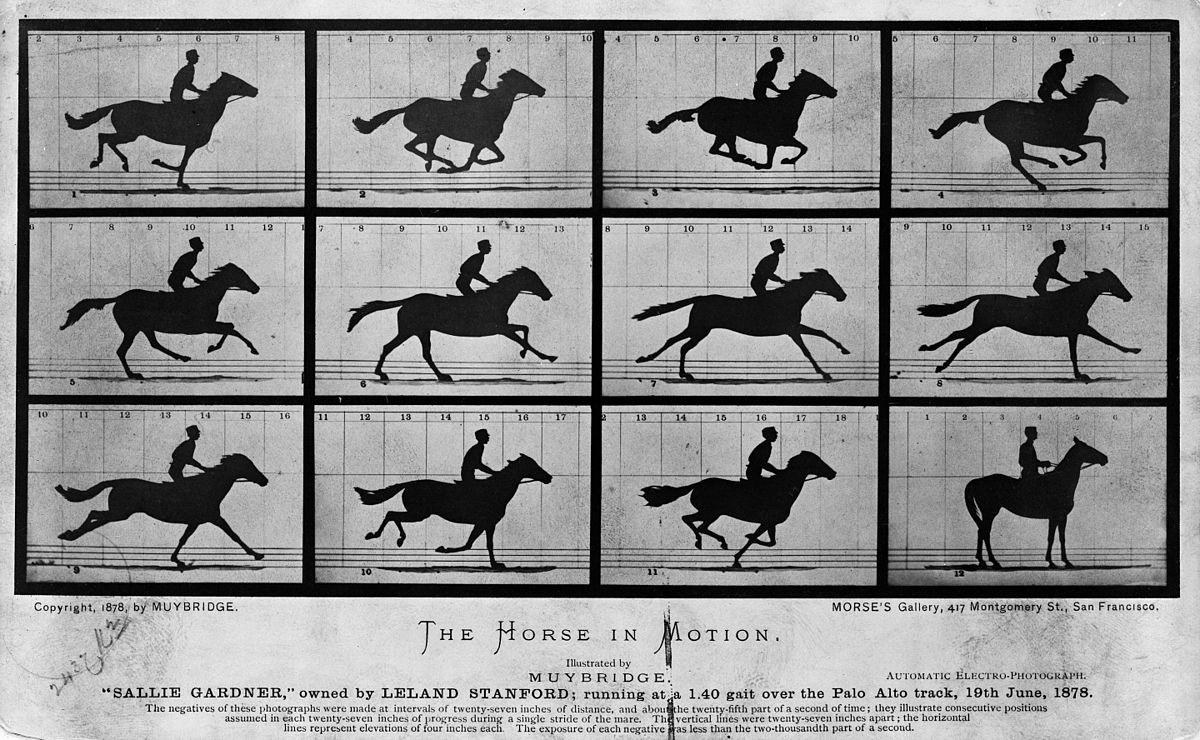

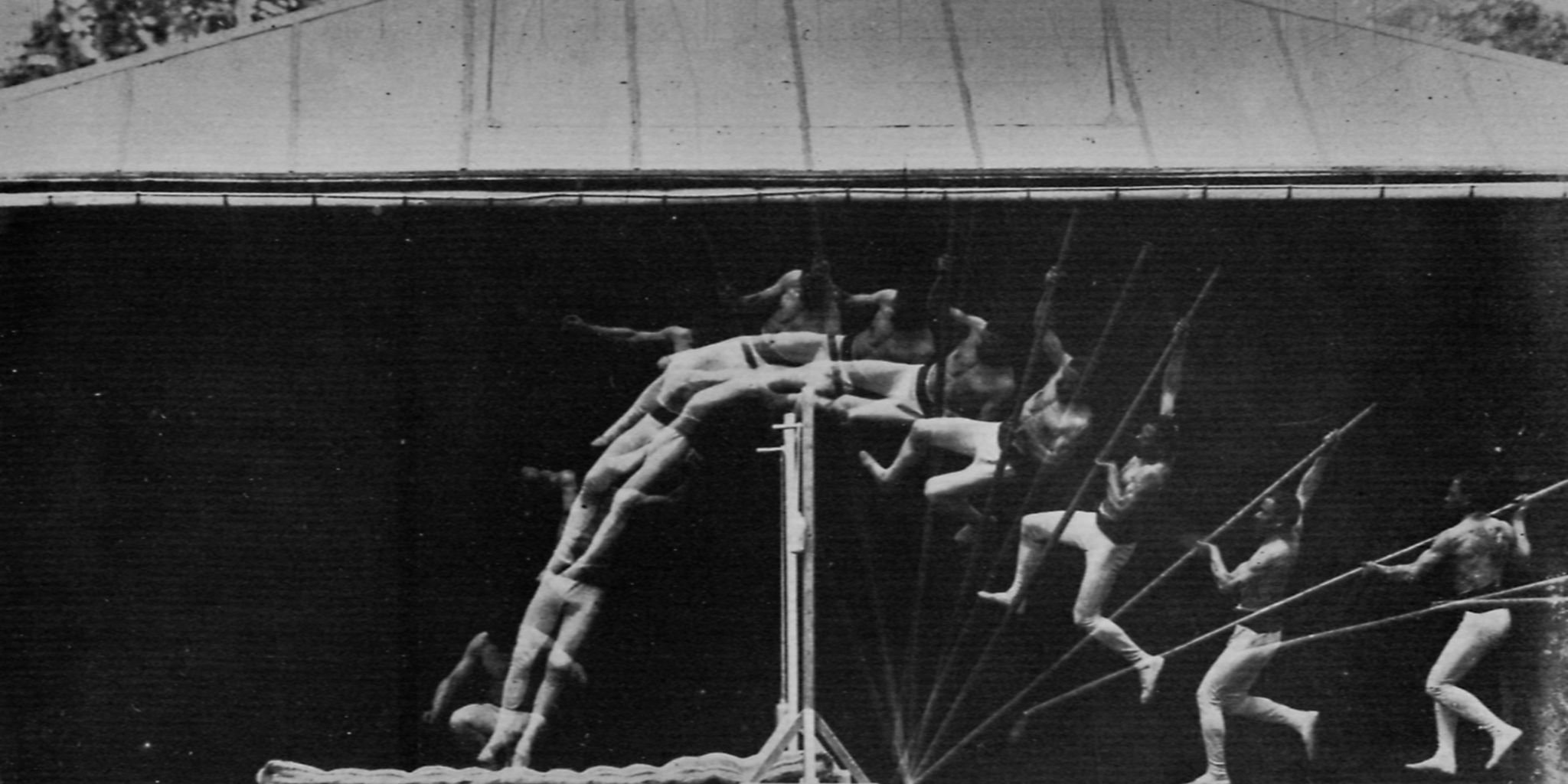

These 20 years, between the 1870’s and late 1890’s, is also when modern animation started to first develop, often hand in hand with film and projection. In 1878, photographer and early film pioneer Eadweard (no, this is not a typo) Muybridge developed a trigger system to photograph a horse galloping, in order to better visualize and understand the way a horse actually moved. Up until that point, people thought that horses moved with their front and hind legs outstretched - the way that rocking horses are usually positioned. The images of the horse in-motion that Muybridge captured - with all 4 legs in the air at once AND with them folded under the its body - was so shocking that people thought it was fake. So, he had to do it multiple times, and still people didn’t believe what they were seeing.

On a side note, I think this anecdote is also a pretty powerful statement to how much the technologies that produce modern images impact us at multiple, even subconscious levels. I can’t imagine how it could ever be shocking or unbelievable to see a still image of a horse mid-gallop, however, since I barely interact with horses in real life and do not possess super-human eyesight or visual acuity, almost my entire basis for how I understand and perceive a horse’s movement is informed by images, video and slow-motion technologies. In other words, the way I “know” a thing in real life is more through images of that thing, and less through actual experience.

For Muybridge, animation technologies began to intersect with his projects and pursuits in a few interesting ways. First, when Muybridge was trying to develop a technique to “play back” his photographs of the horse in motion, he adopted Phenakistoscope technology. Phenakistoscopes were devices that animated discs of drawings through slits for individual viewing. These animation artworks have been experiencing a recent revival and are finding new audiences / viewers through digital animation, particularly as animated GIFs. Back in the 1880s, in order to project his images with this device using light, Muybridge rigged one with a spinning glass disc instead. The process of embedding photos into the glass, however, distorted them so much that an artist had to re-draw them directly onto the glass.

Below are some original animated Phenakistoscope discs, as well as some contemporary ones that have been adapted to work with turntables. Make sure to watch the second video animation, which features multiple disc animations edited together.

130-ish years later, this is essentially the analog equivalent of what you are all doing this week for Project 1 - rotoscoping photographic images taken in succession, then creating an animation from these drawn graphics. Muybridge dubbed this technology a Zoopraxiscope, and it was the prototype for the film projectors used by Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers to publicly exhibit the first “motion pictures” in 1896. So, from one perspective, the first projected films were made possible by animation technology as well as animation techniques. Before going further into how animation techniques have expanded in some ways with the technologies that drive them, I want to show what some argue were the first attempts to create "moving images" or animations: cave drawings.

2.4 Innovation, Invention and Animation

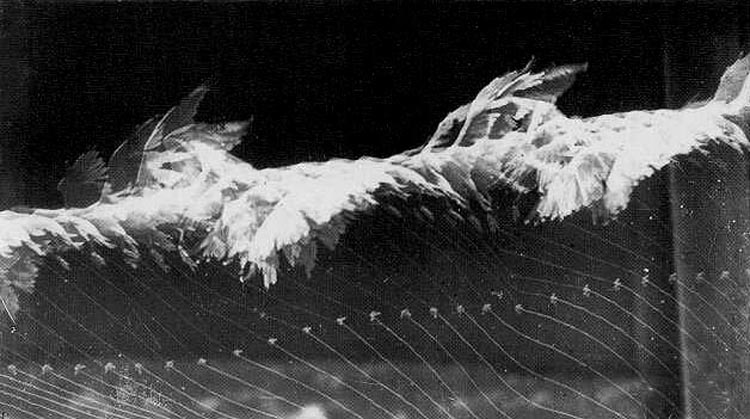

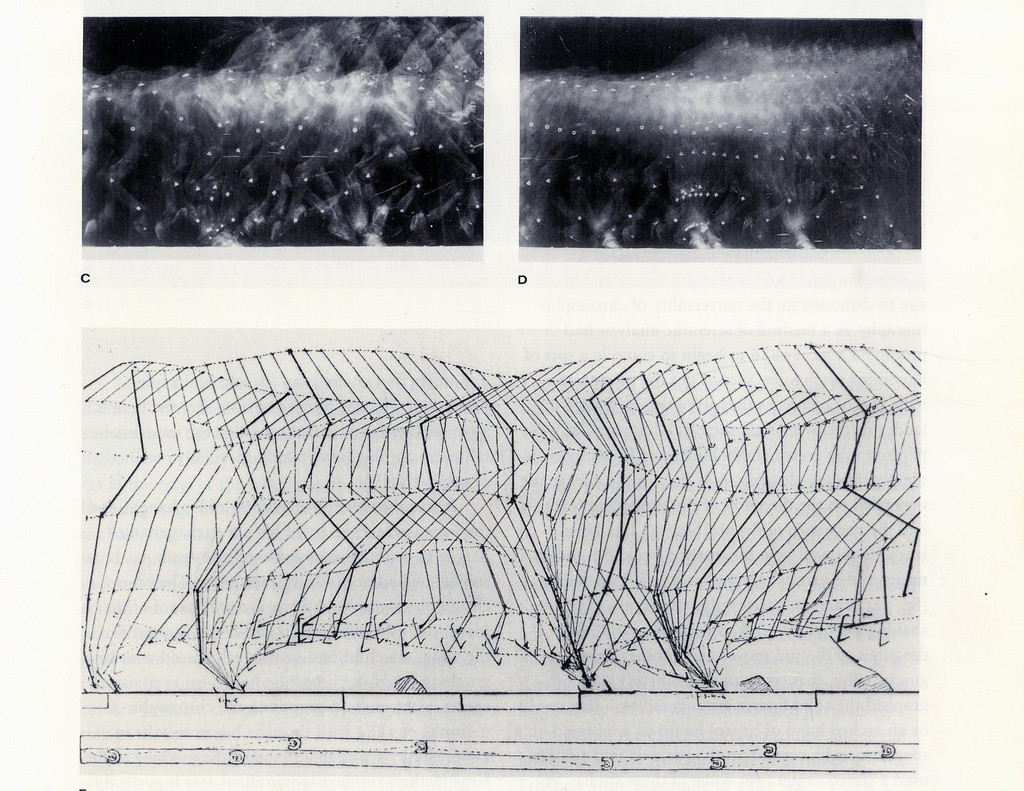

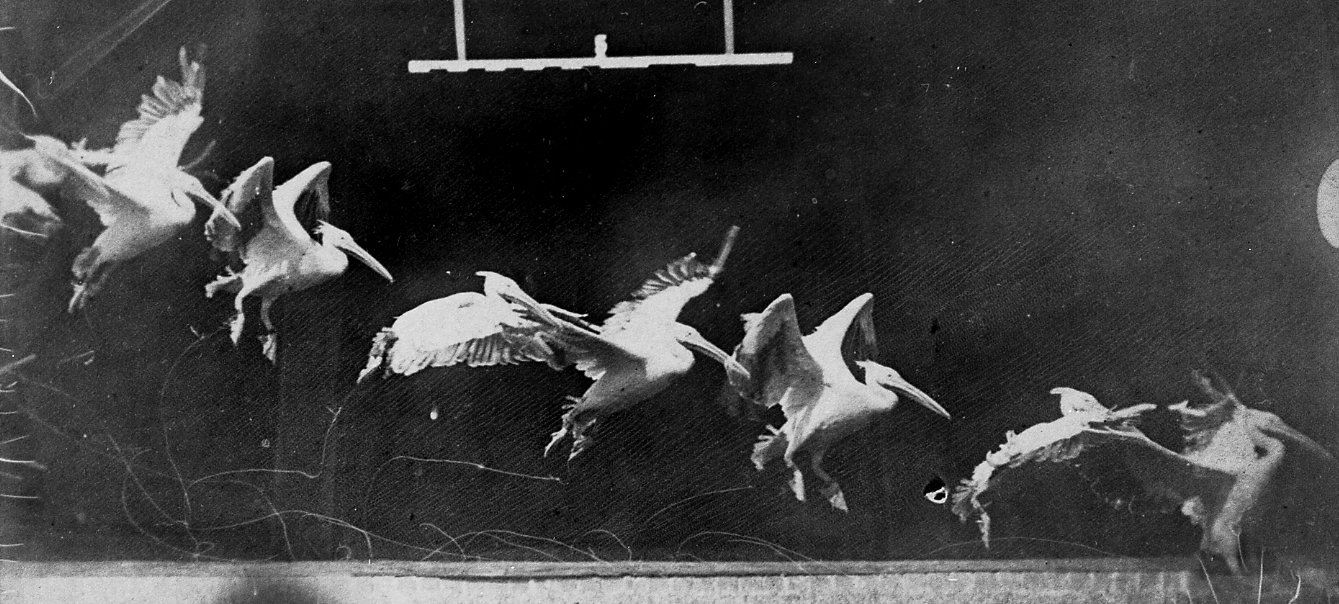

At the same time that Muybridge was developing techniques to photograph horses in motion, Etienne Jules Marey was also busy developing different photographic technology to capture movement that had a lasting impact on film and also animation. Marey identified as a photographer and a scientist, I’m not sure if he ever considered himself an artist, but his contributions to the art worldMary invented a “Photographic Rifle” that he used to film birds in flight at 12 frames per second all the way back in 1882. This camera exposed images onto a disc of film similar in design to the Phenakistoscope.

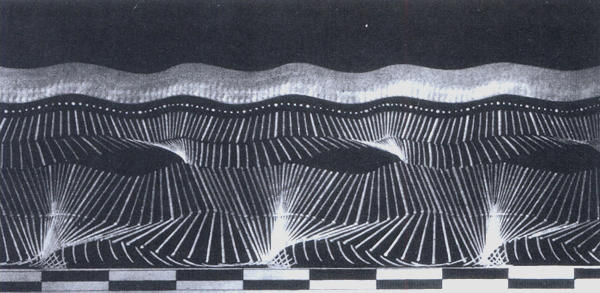

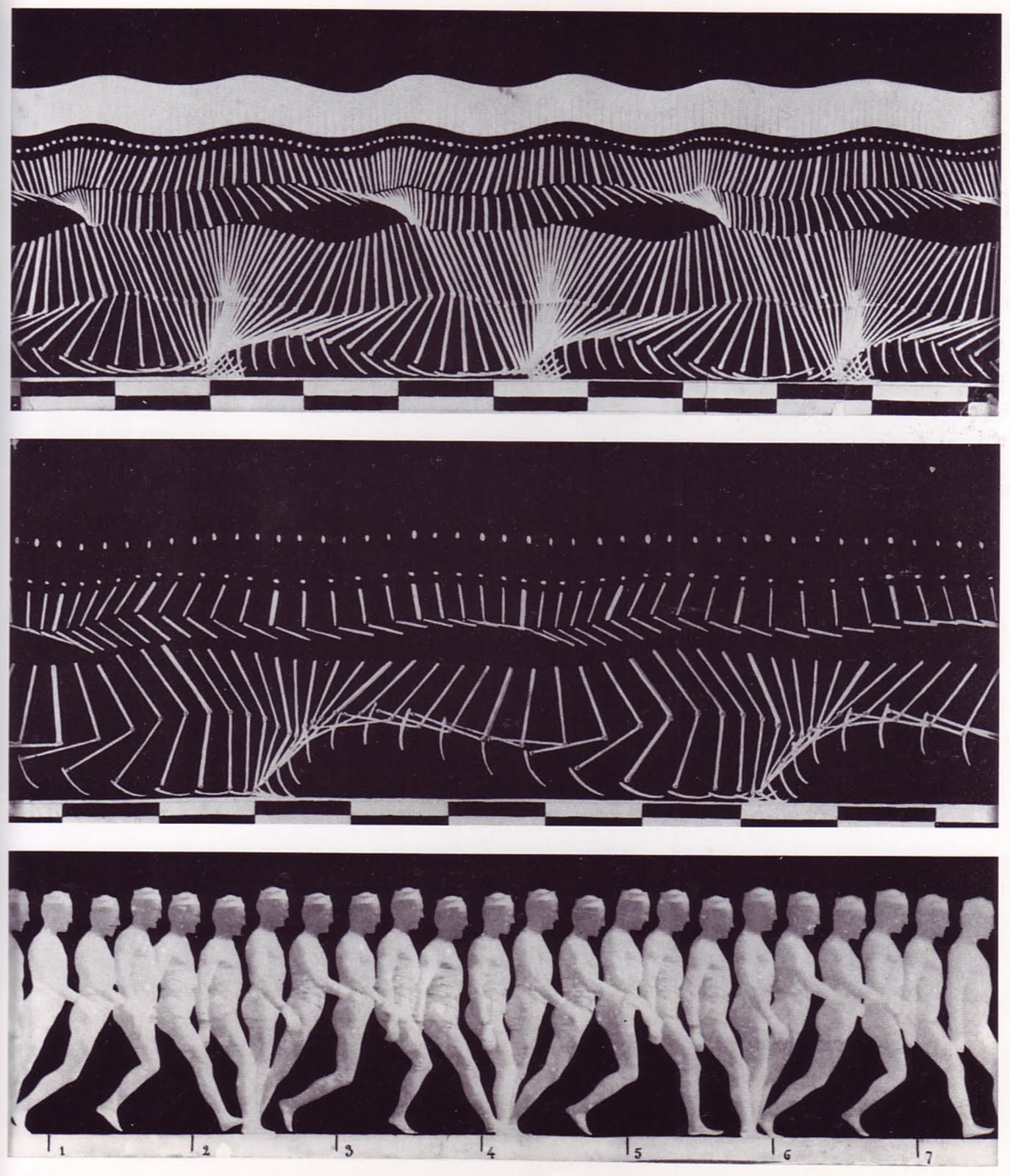

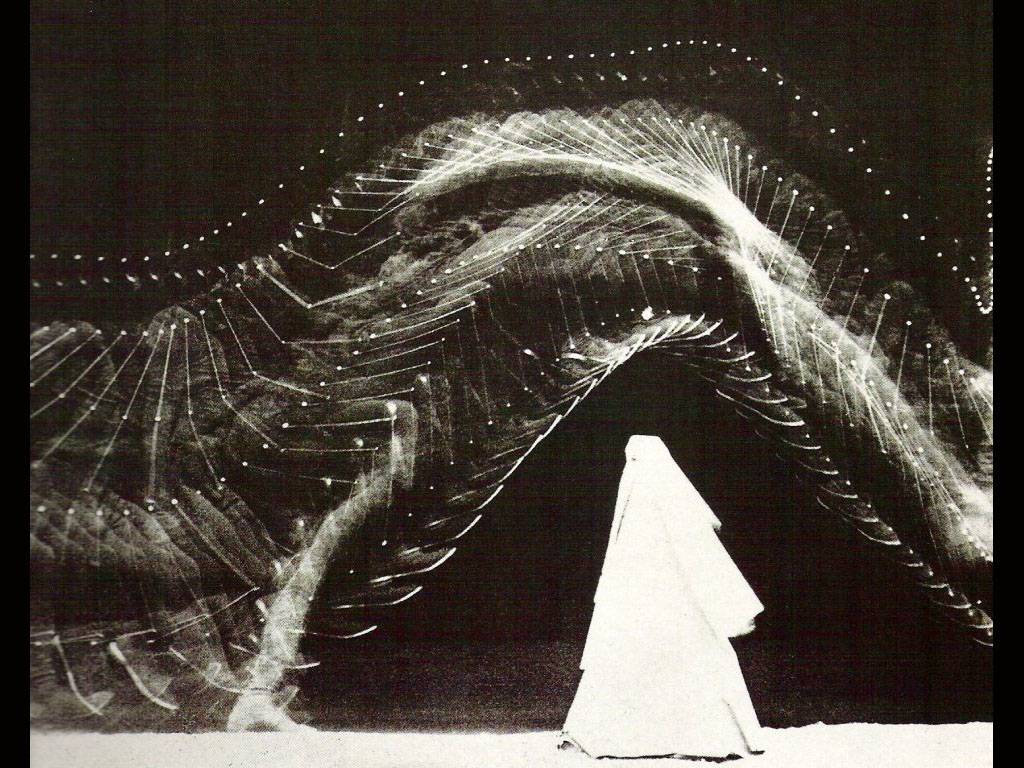

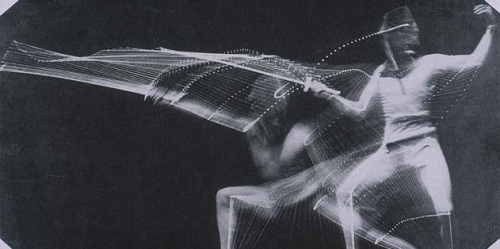

In order to exhibit these images and the motion they captured, instead of trying to create a “moving” image, Marry applied a photographic print process that exposed and over-layed all of the images onto a single print. While these images were “still”, they demonstrated a dynamic sense of motion and energy - I would argue that these images convey more movement than some videos today. They were also closer in format to the modern filmstrip run through a camera and then a projector than Muybridge’s glass discs.

Beyond these technical advancements, Marey’s direction and conceptual approaches to motion capture and exploring movement also had lasting connections to and intersections with animation (even if they weren’t all fully realized or recognized until now). The way he set up and photographed many of his subjects - in all black with white stripes against dark backgrounds - produced abstract, geometric, graphic photographs and prints that resemble something painted, drawn and/or constructed. His explorations with movement are similar to the motion studies and character development that animators employ today - for example, the observation methods Pixar animators utilized in order to animate the characters in the short film Piper. These setups also somewhat resemble - at the very least in concept - the motion-capture process employed today, and many of his visuals are similar to the wireframe visualizations that are often the intermediate outputs between capture and final animation.

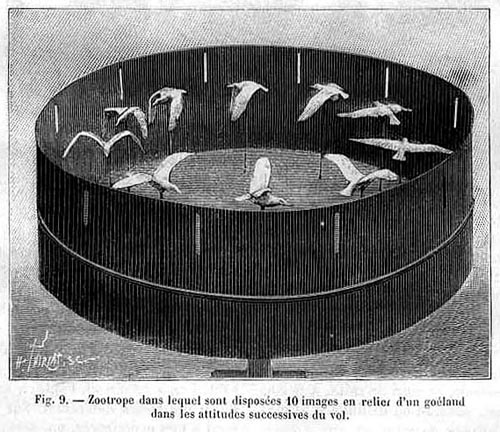

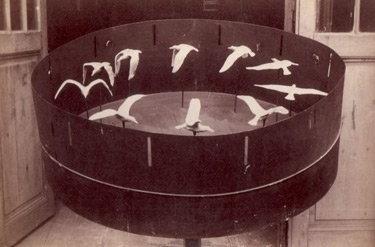

Marey also worked with Zoetrope technology - an early physical animation device that inspired the Phenakistoscope. While he did not invent this device and process, he innovated it and pushed its capabilities by creating a zoetrope drum that “animated” physical, three dimensional objects - in his case, plaster birds. With this innovation, Marey, in the 1880’s, developed a conceptual prototype for 3D animation. Presently, many 3D animation studios and animation artists are beginning to explore this technology further, pushing what is possible by using 3D printers and sometimes incorporating projection and light vector lasers. I believe this revival and new exploration of a century old device is another example of how technology in art-making is less of a straight line of progress and advancement, and more of a cyclic progression, where different processes and techniques will circle back again and again, and each time they do they are pushed and developed a but further.

2.5 Frame Animation / “Cel” Animation EXAMPLES

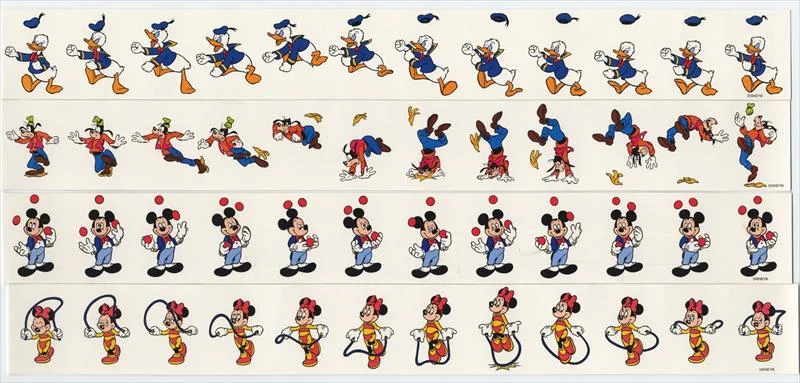

Frame animation is the type of animation used to animate classic films and cartoons from the 1900s on, including Disney animated films. These animations are composed of thousands of still frames of drawings or paintings, each one a fraction of the movement and motion they convey. Traditionally, each frame was painted or drawn on a sheet of transparent celluloid - which is where the “cel” term comes from - so that different elements could be layered on top of one another, like a character moving on top of a still background. Each of these final frames - which might have contained multiple layers - were then composed, and photographed in order to transfer to film.

This process has obviously changed using digital tools, but the principle remains the same. Most animated gifs are frame animations, like the ones used in this interesting collaboration project. Exercise 8.1, for example, is a frame animation that also employs “rotoscoping”, which is a technique that bases illustrations directly on still film or video frames. Many contemporary animators use the frame animation process, both in analog and digital (or a combination of both) forms. Frame animation typically runs “2 up” at 24 frames per second (FPS), meaning that there are 2 identical frames running in succession for normal speed movements and actions, and then higher speed movements will be animated 1 frame at a time. This technique allows different characters or objects to easily move at different speeds within the animation - so things like jet packs and roadrunners can appear to go faster than anything else in the frame.

Below a series of frame animation GIFs made by artist Matthais Brown

The animations below are all contemporary frame animations that are compiled with digital animation software. The images themselves are a mix of hand-drawn, digitally drawn, and digitally colored or effected illustrations. Many of these animations also deal with "transformation" themes.