ART 80T - MODULE 6 - DIGITAL VIDEO + FILM

VIDEO - REMIX, RE-CREATIONS, STREAMING + EDITING

INTRODUCTION 6.1

This module we will be wrapping up the module content for the course and looking at digital film and video. I have to admit that the material was a bit daunting to develop for this module, because digital video is a hugely expansive topic, as both an art form and a part of our contemporary digital culture and media culture. Since it is pretty much impossible to cover this topic in a week, or a quarter, or a year, or multiple years (UCSC’s Film and Digital Media Ph.D program, for example, is designed to be completed in 6 or more years), I am going to instead present on some very specific, topical aspects, including one that relates to the this Module's exercise.

This will be less of a broad survey, and more of a zoomed-in approach. I will be discussing a few relevant ways (among many) that artists are currently engaging with the digital video format, and using digital video editors and digital video applications. I have chosen these different specifics based on not only what relates most to this course and the previous content we’ve explored, but also what is happening right now in the world of digital video and digital media (and, well, the world, in general).

6.2 DIGITAL VIDEO - The Very Basics

To preface these discussions, I want to first establish a brief timeline and define a few aspects and features of digital video that are integral to understanding how this specific technology differs from analog film and analog video in form, creation, manipulation, and distribution. This relationship between the technology and the medium - something we’ve encountered throughout this course - has a huge impact on not only how artists produce digital video and utilize different digital tools, but also what kind of artworks are produced, and the way that viewers watch, and are effected by, these artworks.

Above left to right - a late 1980's entry-level analog video camcorder and Hollywood director Michael Bay using an iPhone camera to capture video some 30 years later. Think about how these two photos might evidence how digital technology and media have changed not only how we document our surroundings but how we think about media.

Digital video and video editing tools became more accessible to individuals and artists working outside of film or video production houses starting around the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, with a few entry-level applications like Apple's Final Cut Pro and digital video cameras that still used (digital) tape, but could be connected to a computer and transfer video files via a digital cable hook up (Firewire on Apple computers) without needing a separate (and expensive) transfer set-up.

Digital video was made infinitely more accessible from 2005 - 2008 with 2 key technologies: YouTube in 2005, and the debut of portable video capture with the iPhone 3G circa 2008. Prior to these two technologies, artists and filmmakers wanting to work with digital video faced two very critical challenges.

Digital video cameras were still very cost-prohibitive, ranging from $800 to $1500 for even the most basic devices and low quality film capture.

Distributing (and archiving) digital video over the internet was bandwidth intensive, even for low quality videos, and it was decentralized in both format and location.

A late 1990s screenshot of the Real Player for windows - this was one app used to both play and access internet videos. Check out that amazing GIF resolution.

So, before these two technologies were developed, not only was it difficult to shoot / capture video and edit it, once something was produced, there was no way to distribute it to a wider audience (or, in most people’s cases, ANY audience). These issues have changed rapidly, and still continue to change almost daily while remaining a vital component of of the digital video medium - that is why I will be looking at streaming technology - primarily YouTube - later on.

Digital video’s digital format is another key element to remember looking at the artworks in this module. Digital video - unlike physical film or analog video tapes - can be easily edited, copied, and recombined. Additionally, digital video is convertible and - by now, at least - has a standard file type. While there are many different types of video files, and ways to compress these files (also known as codecs), most video players + editors recognize and can work with these standard sets. Finally, there are now also many processes for “digitizing” older analogue videos and films. Check out this link to the Prelinger Archive for a huge collection of digitized films. Once in a digital format, these older created works can be re-edited, or recombined.

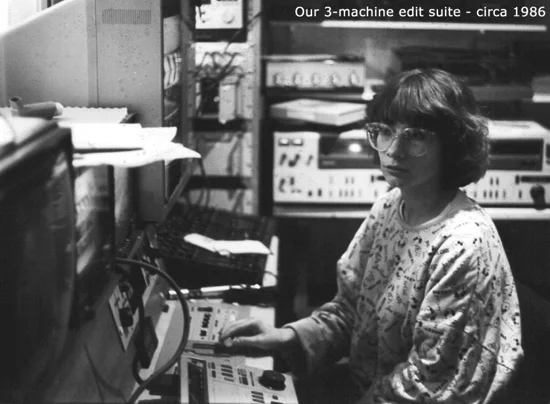

Analog Video Editing Bays - these setups were used to edit video captured on magnetic tapes through a complex process of transferring, recording cuts, then re-recording, all based on a physical timecode.

Since this field is so expansive, the majority of works in this lecture are going to be directly engaging with one or many of these key technological factors (ease of editing, ease of Distribution + streaming and relatively low cost video capture devices ). As you are viewing the works and videos below, note how each artwork, digital tool / platform or technique engages with and/or addresses these core aspects of digital video.

6.3 Digital Video: Re-contextualizing + Re-imagining film + video narratives

The digital technologies used to capture, edit and distribute digital videos are key factors influencing a category of artworks and video projects that take existing films + videos and alter them in some way that influences or changes their original meaning. What was once limited to artists and filmmakers with advanced technical knowledge, high-end equipment, and access to expensive programs and tools, now can be done at a near-professional level relatively quickly and inexpensively by a larger number of artists and filmmakers. This expansion of video editing technology and tools has, therefore, opened up the field for more video artists to explore the idea of re-contextualizing film and video, which, in turn has impacted these works themselves. I will be breaking up this category into smaller groupings of "Remix", "Re-creation" + "Reference" below - keep in mind that these all fall under the umbrella of re-contextualizing / re-imagining.

Re-creation

Re-creation as a method for understanding film and video artworks is something that I believe has only just starting to be explored as its own, viable art-form. Digital editing tools - as well as digital platforms for sharing and posting these artworks - have helped this practice gain legitimacy in the "art world". I sometimes have a hard time distinguishing re-creations from remixes, because they share many common principles and outcomes, but my general rule of thumb is: a re-creation builds on the narrative of the source material, usually changing it, altering it or adding to it from the outside, by merging the new artist’s ideas with those of the original piece. Remixes on the other hand, tend to first dismantle, then re-build, changing the meaning more from within. As with any of the categories I have proposed in this course, there is a lot of overlap between these two, and many artworks will exhibit components of both.

A screenshot from the Star Wars: Uncut website, which allows film makers to organize which clips they will be re-creating

To begin this discussion, let's look at a newer form of re-creation that has surged in In the past few years - crowd-sourced re-creations. These are usually shot-for-shot recreations of films or TV series compiled from hundreds or thousands of clips - some only lasting seconds or minutes and often times produced by different filmmakers or teams. One such re-creation, entitled "Star Wars: Uncut", features entire Star Wars films recreated by hundreds of artists and filmmakers. Follow this link to view how the creators of this project were able to organize and direct crowd-sourcing in order to complete every scene, and to also watch the entire movie. This is a video artwork that requires several of the affordances that digital video offers, from the ease of capture (filming), editing and adding effects to the ability to easily share and distribute videos across networks and streaming platforms.

I believe these types of re-creation films add to their original narratives by exhibiting the infinite number of ways to tell a story and exploring the viewers’ relationship to a particular story or narrative. Watching a known narrative be communicated in new ways can allow for new insights within the original story, once again changing the meaning of the original story or subject matter. Note that the film below, Star Wars Uncut: The Empire Strikes Back, is based on Star Wars V, and is posted by the official Star Wars YouTube channel even though it was generated independently of the Star Wars franchise. What is your take on this official endorsement? Does it change your interpretation of the Empire Uncut, knowing that it is supported by Disney and company?

Sticking with the Star Wars theme but jumping back a few years, the next video artwork I’d like to discuss is a fake trailer created for Star Wars Episode II in 2002, which was posted on fan sites and movie-rumor sites (this was before the era of blogs and YouTube) a few months before the actual trailer for the film was released. This re-creation was produced with digital tools and digitized video taken from different films that had similar action scenes and/or actors slated to appear in the actual Attack of the Clones.

I remember first watching this with a feeling of excitement - even though I knew it was fake - because it hinted at narrative elements pulled from Star Wars canon that I wanted to see more of (like 4 Boba Fetts), and I had heard real film would explore. I figured that if someone could create a trailer this compelling with Final Cut 3 and a few added Lightsaber FX, the real movie was going to be amazing. After the actual trailer was released, even though it was obviously more polished, special-FX-laden and composed with footage from the actual film, I was somewhat disappointed. Part of this might have been the source material, however, I think a lot of my disappointment was that the narrative and images I had created in my own imagination - in anticipation of the actual film, fueled by a few suggestions introduced by the fake trailer - were actually more interesting than what ended up being shown in its entirety. In this way, re-creations can sometimes expand on its source material by providing alternative narrative for viewers to fill-in on their own.

An inverse of this narrative-expansion through re-creation can be seen in the short film Breaking Bad: Canada Edition, below.

Here, the original narrative is re-examined and understood from a different perspective after being presented with an alternative narrative possibility. In this way, both a new story is told, and an old story is seen from a new standpoint. This type of narrative re-examination can be further pushed by viewing films or TV series through an entirely different narrative format or structure. This can happen, for example, when seeing a film as a theatrical performance, or, like in the artworks below, an 8-bit Video Game.

In addition to re-creations that mostly work with presenting recognizable narratives in a new format or form, there are also re-creations that aim to challenge the viewer's understanding or perception of a recognizable narrative by discussing that narrative in a new context. Honest Trailers, such as the ones below, are good examples of these types of re-creations. These do more than simply reference, critique and/or parody a film's narrative, because they work directly with both the form and footage to point out components that might not have been noticed by the audience within the original context. In presenting these new perspectives, these types of videos create space for new meanings, and can also cause a viewer to re-interpret how they might have felt about the original film.

REMIX

Remix, as an artistic concept and practice, is not a technique unique to digital technologies - it is essentially collage applied to sound and film, and was originally implemented using analog processes. As we discussed during Module 2, the Dada-ists developed collage as a way to destabilize, recombine and reconstruct a societal structure that had produced World War 1. The idea of remix works with these similar principles - taking apart something “known” and recombining it with different ideas to create new meanings.

Digital video editing tools have multiplied the number of artists and filmmakers working with this idea of remix. This notion of remix can be seen in clip compilations, memes, mashups and other forms of digital recombination. While these types of video collage and remix are often comical and/or absurd, consider how they also work to create completely new narratives. What kinds of stories do you find yourself creating or expanding on when viewing these types of videos? Do they change the way you understand the original tropes, styles, stories and other remixed elements?

Breaking bad as a TGIF Sitcom, complete with laugh track.

A remix presenting Silence of the Lambs as a romantic comedy.

As evidenced above, many of these remixes or mashups take on a comedic approach. Humor, however, does not negate meaning or effectiveness. To me, these achieve a special level of the absurd that is both hilarious and engaging - I am laughing, but I am also understanding the tropes and structures utilized by romantic comedies and family-friendly sitcoms in new and different ways. These videos change the way I might watch a romantic comedy in the future - if a bit of editing and a different voice over can convince me that Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter are enjoying a happy romance in Silence of the Lambs, how much do I really trust or believe the relationships presented in any other romantic comedy?

A recently revived video and film remix project produced by Paul Miller AKA DJ Spooky more fully explores the powerful effects, transformations and re-imaginings that remixing can achieve. Miller “remixed” the film Birth of a Nation, originally directed by D.W. Griffith in 1915. This film, which was the first feature length film produced and shown in the US, supposedly portrayed a narrative of post-Civil War families. It was overtly racist, violently presented Black Americans as “in-human”, and weaponized the film medium as a way to legitimize - and even hero-icize - the murder and terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan against Black Americans.

Referencing the current political climate of 2017, Miller decided to revive this project, entitled Rebirth of a Nation, which he originally began in 2004. Using remix as a conceptual principle in this work, as well as many of his other works, Miller talks about using remix and collage in order to both clarify and identify different systems of oppression operating within our society and culture, and also provide methods for dismantling them. Part of this deconstruction sometimes involves creating something else - a new narrative, or a new idea - but not always a fully realized “solution”. This type of work can be challenging to view - be sure to read through the article here in full, as it presents many of Miller’s intentions in his own words and offers important context, before watching the trailer.

CW / TW: Remixes footage from the original film “Birth of a Nation”, containing racist imagery and re-enactments of Ku Klux Klan anti-Black terrorism.

Optional Viewing: A 2016 Performance of Rebirth of the Nation. See above for CW/TW

Referencing, Parody + Homage

To conclude this category of re-contextualization + re-imaging , I would like to examine 3 different video artworks that reference, parody and re-contextualize existing narratives in a very interesting succession and order. Reference and parody can sometime be hard to distinguish from a re-creation or remix, and parody or homage and reference are often an element of remix or re-creation videos. In many situations, including the videos above, there is also overlap. For this discussion, I am focusing on these 3 videos because while they heavily reference original materials and narratives and also create new meanings, their forms are not as heavily influenced by digital technologies as the remix + re-creation videos above. These filmmakers most likely utilized digital editing and digital capture, but the digital medium has less influence on the form - there is less of a focus on using digital affordances to deconstruct and/or re-assemble.

The first video, Ever Is Over All, was created by Swiss video artist Pipolotti Rist in 1997. The second is pop singer and artist Beyonce’s music video for Hold Up, a track off of her 2016 album Lemonade. Neither Beyonce, nor the video director, have acknowledged directly referencing Ever Is Over All, however, the visual similarities at certain points is undeniable, even it was purely unintentional. The third video is a direct re-creation video of Hold Up produced by the team behind the Netflix series the Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. In this video, actor Titus Burgess performs in full character as Tituss Andromedon, re-creating Beyonce’s Hold Up video and lyrics. The actor has clarified that the video is not intended to be parody or satire, but an homage that works within the show’s overall narrative and as a part of this character.

Go to about 20 seconds

Go to 1:45 minute mark

Go to 30 second mark

I think these artworks are all interesting viewing both as individual video and film artworks, and as referenced and/or inspired narratives or homages. I also wanted to post these examples to show that this concept or re-imagining is not limited to lesser-known artists re-creating more well-known works. When watching these videos, note your own responses and consider the following - If you had seen Ever Is Over All previous to Hold Up, did you notice the similarity? Do you think that Hold Up is less powerful after seeing Ever Is Over All, or does it change the narrative enough that it is simply an effective sample or reference? Alternatively, do the visuals from Ever Is Over All take on different, more powerful meanings in a more narrative-driven context, as they are presented in the Hold Up video (when accompanied by both the lyrics and also the narrative behind the album as a whole)? Does the Titus Burgess video invoke more parody or homage in your opinion? Does it make this piece more or less powerful that the artists involved have expressed that it was intended to be a direct homage? And, finally, how does Burgess' video - released most recently - effect your memory or interpretation of Ever Is Over All, the oldest video of the three?

In other words, what happens when an artwork is an homage to another artwork that borrows visuals from another artwork? Does that change the original source material or narrative? Is this starting to remind anyone of Back to the Future? (if Rist hadn’t ever made Ever Is Over All, what would Tituss Burgess be acting out in the homage video?…what would a totally different form of the Hold Up video look like? And, if you had never seen the Ever is Over All video, is it possible to see it now without referencing the Hold Up video, even though, time-wise, it could not have referenced that video?)

Remember that while I consider these videos to be examples of a re-contextualized narrative, they are less linked to editing and capture aspects of digital video, and these components have less influence on the 3 videos' final forms. References and parody like this have existed long before digital technologies, however, with the advent of digital streaming and user-centered distribution platforms like YouTube, Vimeo and now even Tik-Tok, videos like these are easier to distribute and access. While these last 2 videos could have been made 20 years ago, there wouldn't have been an easy way to watch and distribute them. If YouTube didn't exist, there is a high possibility that the Burgess' video would not have been made in the first place, because without YouTube, there would not be a way to distribute a video like this to guarantee enough viewers to offset its high production cost. Additionally, less people would have been able to view the Beyonce video, rendering the parody ineffective. From this standpoint, even with more traditional parody or re-creation video forms, digital video technologies still have a substantial impact on what types of videos and films are being created.

6.4 YouTube

Before continuing with this lecture, please read this article about YouTube, (Image Link Above) and watch all of the videos included within it. This is a very insightful historical and contextual look at YouTube, written and produced by The Telegraph, that explains and contextualizes several aspects of YouTube. For this article, pay close attention to the “Education” section, and consider how YouTube has impacted art-making by streaming tutorials for different tools and processes that might be inaccessible otherwise, connecting back to the course theme of viewing the internet as its own “digital tool” / resource for contemporary artists.

Now that you have completed this article, absorb these facts from Mashable in 2011

More video content is uploaded to YouTube in a 60 day period than the three major U.S. television networks created in 60 years.

And then again in 2014:

In the one minute it takes you to read this text, 100 hours of video will be uploaded to YouTube. That's 250 days of video every hour, 16.4 years of video every day, and six millennia of video every year.

YouTube has essentially reversed the flow of video and media, which is something that has previously remained constant since the advent of motion pictures and television, even as services like iTunes, Netflix and Hulu were being developed. Prior to this, the majority of viewers were only able to access video via television networks, which were heavily mediated and only represented a tiny fraction of the video being captured worldwide. With the advent of YouTube, there was suddenly a centralized location to both contribute and watch video, which has continued to become more and more accessible to more users and viewers across the globe. In my opinion, this new order is far from perfect or in many ways ideal, however, it has caused undeniable artistic, social, cultural and political impacts that continue to resonate with every additional advancement.

As I have discussed before, photographs and videos partially construct and inform our real-world. Recall my anecdote about Muybridge and the horse, and how slow-motion videos of horses are the only way I “know” how a horse gallops, since it is something I cannot see that with my own eye. This phenomenon hopefully explains how YouTube has greatly impacted society and culture - we, as viewers, suddenly have billions of additional videos available to use to construct this meaning and our understandings of our world / reality. And now you will never look at Grumpy Cat the same way again.

Below are a few video works that interface directly with the YouTube platform as a digital tool and a resource for create artworks. They edit and recombine other user-generated YouTube videos in order to create brand new videos. This recombination is similar in principle to what the Dadaist were doing with collage all the way back in 1917 and (what other remix artists were doing in the previous chapter), with one major difference: instead of recombining well-known medias in order to challenge or redefine old meanings and produce new understandings, these videos expand and explore what might be considered “every day” content and re-frame it in ways that tell different, new stories. When viewing these videos, note your response. Do you find the original content more or less interesting after watching these? What new narratives, stories or ideas did you pick up on?

Below, sound and video collage artist Kutiman edits together completely new songs all from user generated content posted to YouTube. His final pieces work both as standalone audio tracks and video / audio collages. He has released two albums of this type of work, and credits each of the original videos he samples on his website.

Life in a day

Life in a Day 2011 directed by Kevin MacDonald is a feature length film compiled entirely of videos shot and uploaded to YouTube on July 24th, 2010. As you might have guessed, this film is available on YouTube in its entirety.

1 Second Everyday

While the two are not directly related, when the 1 Second Everyday (1SE) was released, I immediately thought of Life in a Day - its kind of like the inverse method working with similar concepts. This app cuts together one second of video from each day of the year - it doesn’t access YouTube contributions, yet, but many of these compilations are posted on YouTube and Tik Tok, and I believe its only a matter of time before this starts to be integrated more with other social / streaming media platforms.

Streaming video platforms like YouTube are also undergoing a major evolution in this moment, as Live streaming becomes more and more prevalent and supported. This advancement brings with it a whole separate list of uses, as well as considerations and issues, which I will discuss in the next chapter.

6.5 Live (Life) Streaming Video

Live streaming video - broadcasting video live via data networks or internet connections to other social media or video streaming platforms - is a very recent technological development in terms of integration with existing platforms and accessibility for users without specialized equipment or setups. Facebook launched its Live Stream option in 2016, and YouTube recently followed suit by promoting its live, mobile broadcast option in 2017. These were the two “heavy hitters” in a live stream field that also includes Snapchat and Instagram, and now is joined by slightly related platforms such as Twitch and, of course, with the COVID-19 Pandemic, Zoom. Each of these different applications offer slightly different features, but the concept is mostly the same - people can broadcast live video via just a smartphone with a data connection to a potential audience of hundreds or even thousands.

Different applications like YouTube and other streaming networks and platforms have been working with the concept of “live video” for many years. Webcams capture and broadcast live videos ranging from surf conditions to highway traffic to different animal dens and enclosures. A few years ago, my mom was obsessed with the live feed of a nest of owls, and all of the drama that ensued when the fledglings started flying and falling out of the nest. I will also admit that I have watched my fair share of wolf cams. And puppy cams.

The differences between these technologies and the most current technologies is that they were - and are - mostly one sided, and they required more extensive setups including dedicated hardware like cameras and cabled internet connections on the video capture end of things. The feeds were mostly passive, and viewers could not easily change, or interact, with the live-recorded subjects nor the video itself without a specialized program or installed application.

More recently, YouTube, Facebook and other live streaming networks such as Twitch have included ways for viewers to provide feedback which then becomes part of the live video content. This can be in the form of chat comments, audio, images, other live video and screen sharing. These options provide for more interesting user interactions, as well as more options for creating engaging video content. I believe in the next 2 - 3 years, there will be an influx of creative compelling video-based artworks utilizing these new tools. For now, check out the a few of the live streams hosted at Explore.org’s YouTube Channel, including the live stream below of Katmai National Park in Alaska.

Digital Video, Streaming Video + Social Justice

Accessible live streamed video is an incredibly powerful media with real-world social, cultural and political outcomes that have barely been assessed. There are several groups and organizations who have begun to utilize these technologies to act as a witness in way that protect people’s freedoms and human rights. One such group, witness.org, offers tools, communication materials and workshops on how to use streaming video systems for these purposes. Follow the image link below to this organization to see some of their most recent video projects.

The capabilities of this medium as a tool against injustice and brutality have become especially apparent in the last few years and even the last few months (and weeks). With the renewed protests against anti-Black police terrorism, sparked by the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among tragic numbers of other BIPOC individuals, digital video and digital streaming has been used by many journalists, activists, organizers and citizens to protect themselves and their comrades, and further document violent and terrorist acts committed by law enforcement agencies. It has also been used to film and document the radical actions of protestors standing against these systems of violence and oppression.

Below is a link to an article about Unicorn Riot, a (relatively) tiny grassroots media / activist group that has been tirelessly covering aspects of protests and other actions that have been ignored or less-covered by mainstream outlets.

Mobile live streaming, for all of its complexities, has undeniable potential as a tool for folks working within social documentation, social practice, or any kind of organizing, activist or social justice work. If this is a digital tool you are interested in using to document or witness protests, political actions or other events, be sure to constantly stay on top of how to protect yourself and others. There are many resources for this type of information - this page (which I compiled for a course last quarter) contains a few recommended jumping off points that cover protecting identities of citizens being filmed, and protecting yourself and your data, especially if you are photographing or filming.

Video can be an incredibly powerful medium of resistance and revolution, but as the saying goes, with great power, comes great responsibility, and live streaming or filming the actions of protesters can have serious implications.

Above are two GIFs based on videos capturing the 2017 protest and removal of a Confederate Statue in Durham, North Carolina. These GIFs were widely distributed and shared on Reddit, Facebook and then news media outlets. The original videos document the removal of a Confederate Soldier Memorial Statue by protestors 2 days following the events in Charlottesville, Virginia, over the authorized removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. While these videos document an important and powerful action, they were also used by law enforcement to identify, arrest and charge the most active protesters with what many believe to be disproportionate, felony crimes. These events help explain why now, more than ever, video documentation and distribution is a complex, multi-faceted issue.

Below is a pre-digital video captured and distrubted by a CNN camera crew in 1989. In the pre-digital era, journalists and photo/video-graphers were the first to be targeted and suppressed in protests and actions. How has digital technology changed the social activist landscape now that almost every person present can document and distribute images and video? What does it mean that some of this documentation is being used to identify and charge people?

A CNN crew covering the June 5, 1989, protests in Beijing recorded a man stopping a Chinese tank in Tiananmen Square - this was before digital technologies, but consider the impact that this video has had throughout the world.

6.7 Video + Media Culture

To close out this section, I wanted to address how different live streaming and video platforms, such as YouTube, Twitch and Tik Tok, intersect with other forms of creative media. These different types of media interact with one another, play off one another, and in many instances one technology can be responsible for the popularity of another completely different digital media category. One example of this is how Twitch and YouTube were instrumental in turning the multiplayer game Fortnite into a global phenomenon. Sure, the game play is dependent on networked digital technologies (not to mention the creative digital tools used to create the game itself) but without these streaming platforms to promote the game and build an audience and huge community out of the players, it would be a very different and less popular gaming experience.

Below, screenshots from pro-gamer Ninja's Twitch channel, streaming a Fortnite Duo with Drake - the first stream broke the internet (and the Twitch record for most watched single channel stream)

Lil Nas X’s Old Town Road also perfectly demonstrates this phenomenon. Watch the video below and consider how many types of video technologies were a part of this song’s creation, promotion, rise in popularity and continued success (also, note how they are using yet another streaming video technology to conduct this 4 person interview across the world).

Without all of these video technologies, this song would not have been an popular as it was during summer 2019. And, to bring everything full circle, Lil Nas X also edited together footage from Red Dead Redemption 2 (a video game released in December 2018) to accompany his first version of this song - this music video is another example of video / video game remix. It utilized a game to produce “footage” that was cut together and re-presented in a completely new way.

Zoom and COVID-19

Given the events of the past year with the COVID-19 pandemic, and the lasting affects it will have on so many aspects of our lives, I of course need to mention Zoom and remote video communication technologies in this module. Since we are still very much immersed in and responding to this crisis, it is very difficult to have much perspective when it comes to exploring how Zoom and other video communication technologies have become integrated into a huge range of interactions, including work, socializing, entertainment + recreation, events and, of course, education. That being said, I am hopeful that this course, and this module especially, can help everyone better understand video as a medium, and see how it has been used, and how it might be used in the near future, along with the tools and processes used to shape and present it.

As the pandemic continues, it will become increasingly important to understand how to best and most effectively utilize digital video as a communication tool and medium, along with other digital mediums, formats and platforms. This course was designed and developed as an online course a couple of years ago, so its remote format has always been a core-design aspect, but this is not the case for most courses (and so many other things). Right now, in this moment, artists, designers, filmmakers and so many other creative folks are figuring this out - and as students, you are all at the forefront of this exploration and direction. Below are a few examples of different artists working within the Zoom format since last March - as you watch through these, think of them less as a pattern to stick to, and more as a way that artists have only started to use these tools.

6.6 Video Wrap-Up

So, I know this module has been a bit different from previous ones - I really want to stress that the above categories, videos and artworks are based solely on a few areas that I think are important to address with what is happening right now. The topics I present above do not fit any standard academic framework for talking about "Digital Video" or "Video Art", so, please don't think that to be a video artist, one is limited to re-creations, remixes and filming protests, or that video artists have only been active since 2008 with the advent of the iPhone. There is a huge body of work produced by video artists dating back to the 1960's and 1970's - to check out some examples of more commonly classified "Video Artworks", see Chip Lorde's expansive library of video artworks , or works by Bill Viola and Pipilotti Rist. These artworks and artists exist more within a gallery-based definition and system of video art, with the exception of Chip Lorde's groundbreaking Ant Farm and other media-based artworks, which focused on dismantling and creating art outside of these systems.

As for the works shown in this module - I wanted to provide possible entry points for people in this class, and also offer context for the video media a lot of us consume on a daily basis. For each of these categories and mediums, keep in mind that they are all either incredibly new, or deal with technologies that are constantly advancing or in flux. This means that while there might be less pre-established ways to utilize this technology to create and distribute artworks, there are also less boundaries and expectations. I believe this is a moment in time that artists need to be expanding the use for these technologies in ways that haven’t yet been imagined - and I encourage each of you to recognize the artist, designer, filmmaker, innovator, engineer, radical, scientist, activist and/or creator within to take these tools and apply them in whatever direction or field that means the most to you.