MODULE 7: TIME, MOTION + ANIMATION

Module 7: TIME, MOTION + ANIMATION

7.1 INTRODUCTION

This module we will be looking at time, motion and animation in photography, film, video and other artworks from roughly the past 200 years, with a few examples that date back 30,000 years or so. We will be viewing most of these earlier works as a way to understand some different animation principles, and to also understand how different types of animation and animation techniques have evolved with the advancement of different technologies. Animation (along with other artworks that deal with time and motion) has an interesting relationship with technology that sometimes parallels how contemporary digital media artworks or artworks produced with digital tools are inherently tied to these technologies that produce and/or run them. Exploring these connections and influences can help us understand how all of the digital tools we work with in this course - including digital animation tools - impact the larger world of contemporary art making.

I will also be introducing a few different categories of animation, and then showing a range of artworks that fall within each of these categories. While these are standard ways of classifying different animation styles and techniques, there is always overlap between categories, and there are also terms that can describe slightly different things depending on which type of animation process is being used. I will try to clarify when these discrepancies come up.

Finally, I wanted to let everyone know that this module is a little more time intensive, because there will be more video to watch - the majority of the video links in this lecture will link to actual artwork, as opposed to artists talking about their works. As far as the final exam goes, when it comes to these animations shown in this lecture, I will only potentially ask about the artist(s) name, the primary technique that was used to produce it, and the basic concept and/or subject matter - I won’t be asking anything analytical or about specific narrative details. So - take the time to watch these, absorb their visual characteristics, and, above all, enjoy!

7.2 Early Motion Capture

I, personally, have always defined motion capture as any technique used to somehow visually record motion occurring in real life. The other day when I was writing this I realized that this is also the industry standard term used to identify the specific technology that involves digitally tracking and recording a subjects movements, usually with the aid of a suits with sensors attached to multiple vertexes. In my opinion, this technique is only one way of many to capture and record motion - but I thought I should mention that when I am talking about “Motion Capture” in this lecture and the studio tutorials this module, I am not only referencing that specific technology.

The other reason why I continue to use the term motion capture instead of just saying film and video, is because I believe that those terms also imply that whatever motion was recorded can also be easily (re)“played”. For example, a snap plays as soon as you finish recording it. In the 1990’s, the stop-motion ninja turtle videos I made on my dad’s camcorder would play back right on the little lcd screen, at least for 8 minutes until the battery died and had to be recharged overnight. And, even in the 1970’s and 1980’s, when people were creating works with smaller film cameras, they could watch what they recorded on projectors as soon as the film was developed. This, however, is not always the case with motion capture technologies, even contemporary ones, and certainly not ones that were being developed in the 1880’s

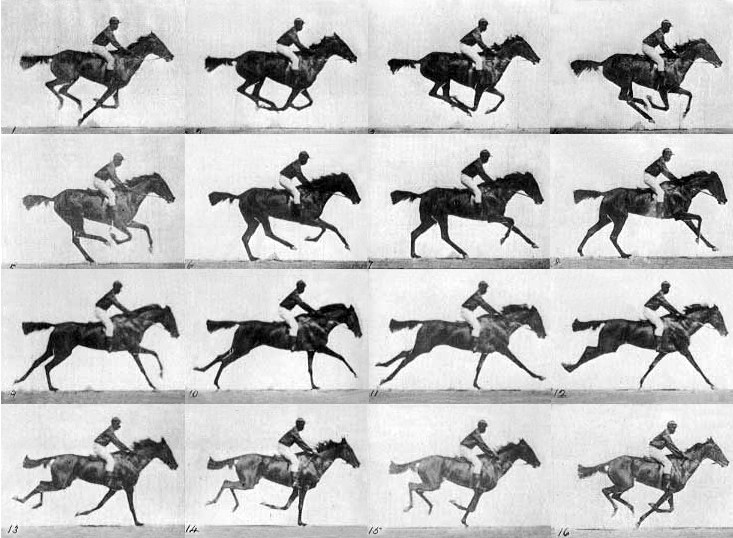

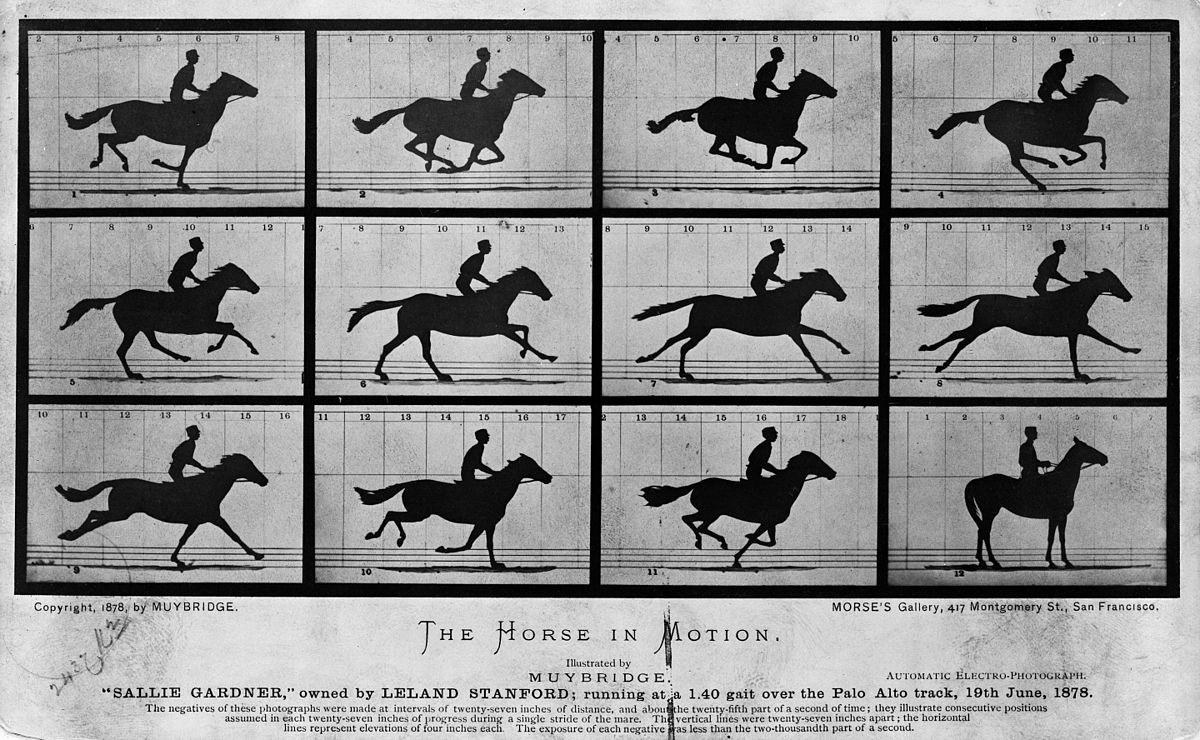

For the early pioneers and artists working with motion capture technology, the cameras developed faster than the playback devices. People were creating cameras and camera setups that could record motion, but they couldn’t easily re-create that motion or play back that motion. So, while still images were able to convey each frame of a horse’s movement in 1878, the technology to project that video wasn’t developed until more than 10 years later, and it wasn’t until 1896, almost 20 years later, that film and projection first started being considered more paired processes, technologies and artistic mediums.

7.3 Enter Animation

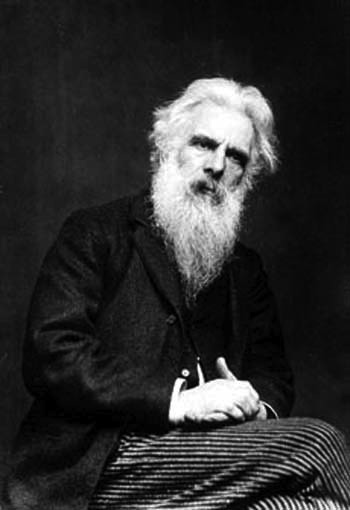

These 20 years, between the 1870’s and late 1890’s, is also when modern animation started to first develop, often hand in hand with film and projection. In 1878, photographer and early film pioneer Eadweard (no, this is not a typo) Muybridge developed a trigger system to photograph a horse galloping, in order to better visualize and understand the way a horse actually moved. Up until that point, people thought that horses moved with their front and hind legs outstretched - the way that rocking horses are usually positioned. The images of the horse in-motion that Muybridge captured - with all 4 legs in the air at once AND with them folded under the its body - was so shocking that people thought it was fake. So, he had to do it multiple times, and still people didn’t believe what they were seeing.

On a side note, I think this anecdote is also a pretty powerful statement to how much the technologies that produce modern images impact us at multiple, even subconscious levels. I can’t imagine how it could ever be shocking or unbelievable to see a still image of a horse mid-gallop, however, since I barely interact with horses in real life and do not possess super-human eyesight or visual acuity, almost my entire basis for how I understand and perceive a horse’s movement is informed by images, video and slow-motion technologies. In other words, the way I “know” a thing in real life is more through images of that thing, and less through actual experience.

I am going to discuss more riveting insights and tangents about early photographic motion capture and film next week, however, for Muybridge, animation technologies began to intersect with his projects and pursuits in a few interesting ways. First, when Muybridge was trying to develop a technique to “play back” his photographs of the horse in motion, he adopted Phenakistoscope technology. Phenakistoscopes were devices that animated discs of drawings through slits for individual viewing. These animation artworks have been experiencing a recent revival and are finding new audiences / viewers through digital animation, particularly as animated GIFs. Back in the 1880s, in order to project his images with this device using light, Muybridge rigged one with a spinning glass disc instead. The process of embedding photos into the glass, however, distorted them so much that an artist had to re-draw them directly onto the glass.

Below are some original animated Phenakistoscope discs, as well as some contemporary ones that have been adapted to work with turntables. Make sure to watch the second video animation, which features multiple disc animations edited together.

CONTEMPORARY PHENAKISTOSCOPES

130-ish years later, this is essentially the analog equivalent of what you are all doing this week in the studio exercise - rotoscoping photographic images taken in succession, then creating an animation from these drawn graphics. Muybridge dubbed this technology a Zoopraxiscope, and it was the prototype for the film projectors used by Thomas Edison and the Lumiere brothers to publicly exhibit the first “motion pictures” in 1896. So, from one perspective, the first projected films were made possible by animation technology as well as animation techniques.

7.4 Innovation, Invention and Animation

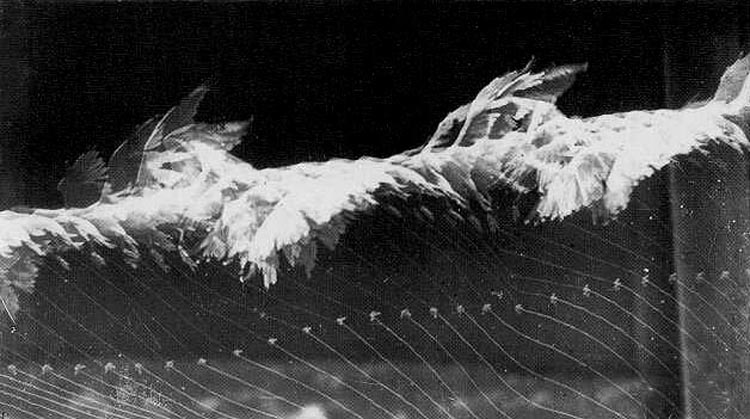

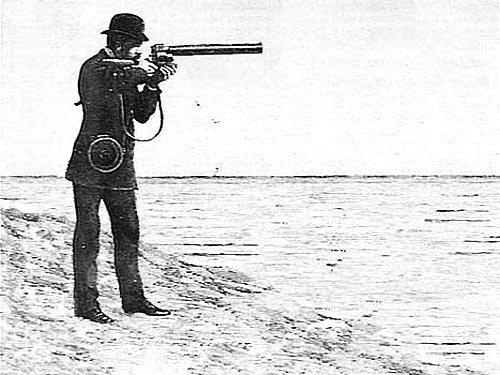

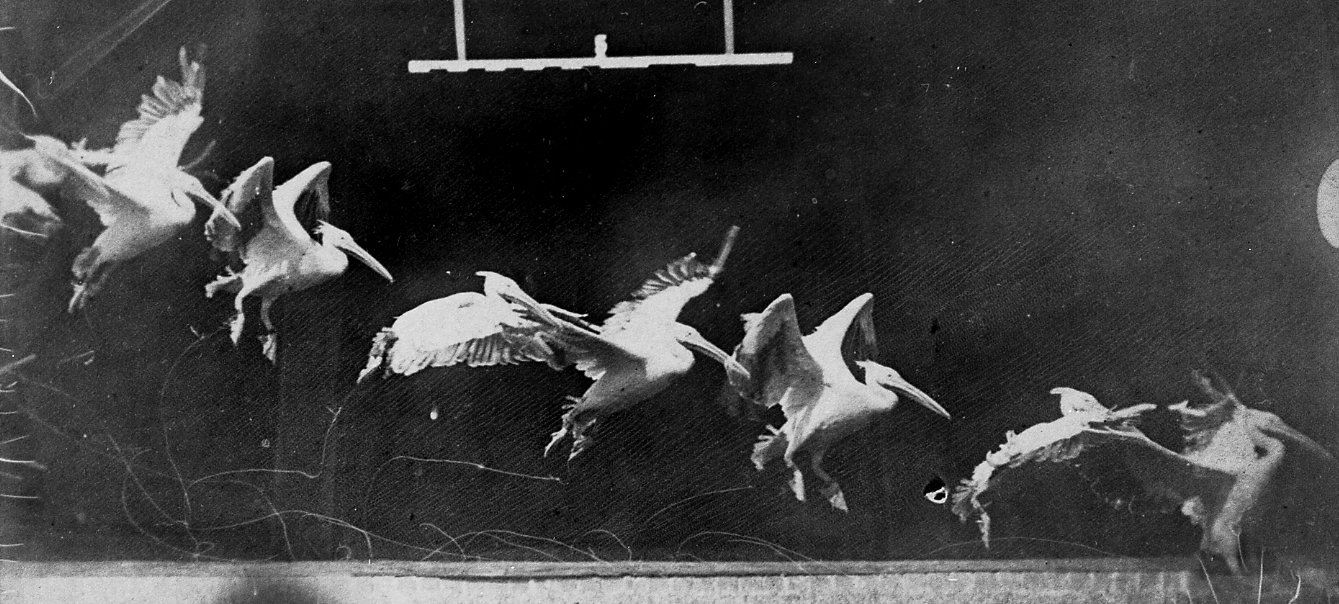

At the same time that Muybridge was developing techniques to photograph horses in motion, Etienne Jules Marey was also busy developing different photographic technology to capture movement that had a lasting impact on film and also animation. Marey identified as a photographer and a scientist, I’m not sure if he ever considered himself an artist, but his contributions to the art world are extensive. Marey invented a “Photographic Rifle” that he used to film birds in flight at 12 frames per second all the way back in 1882. This camera exposed images onto a disc of film similar in design to the Phenakistoscope.

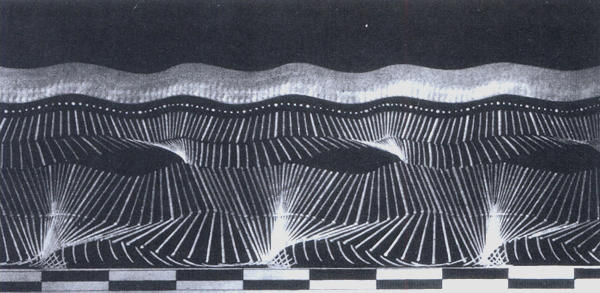

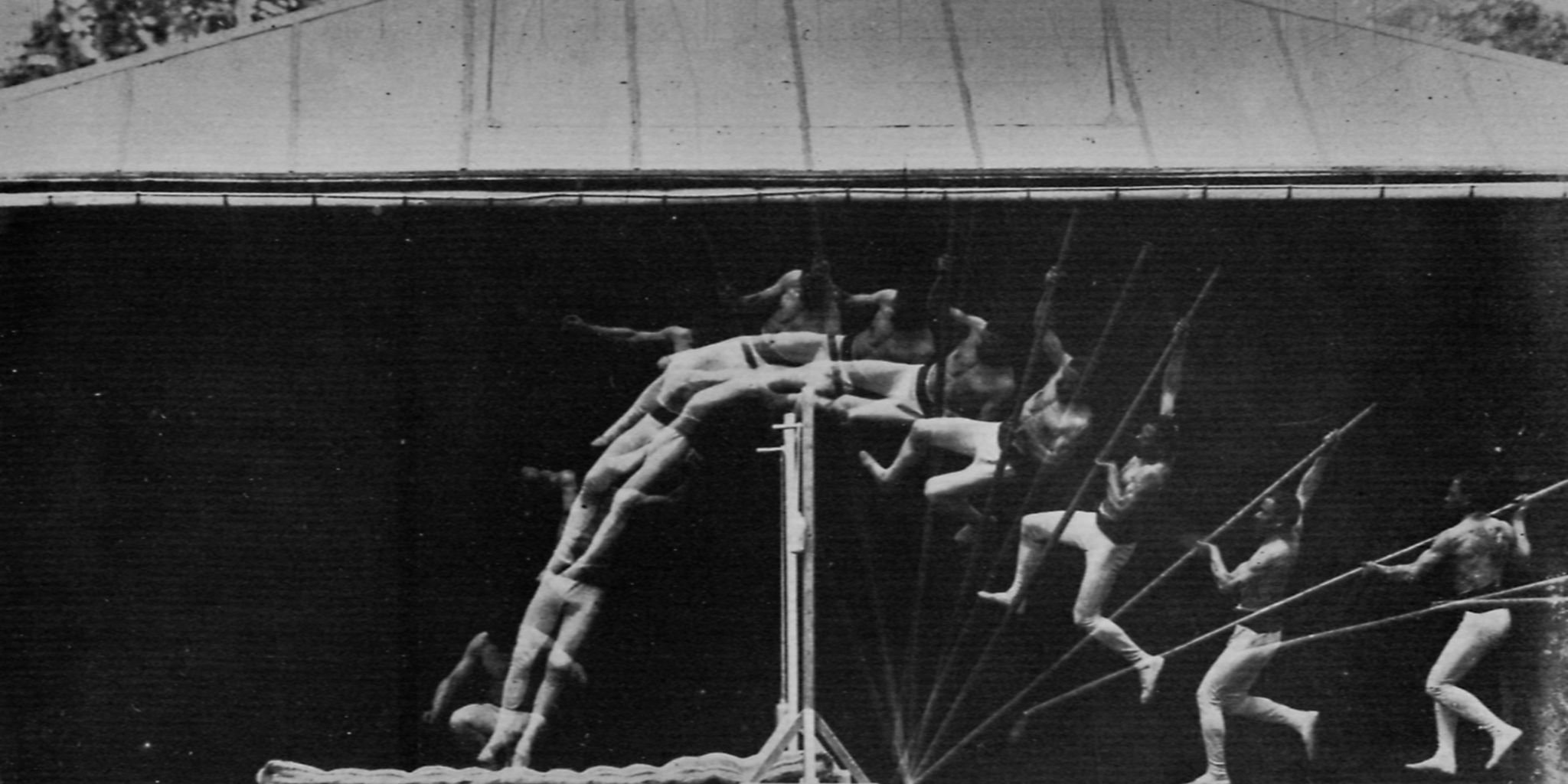

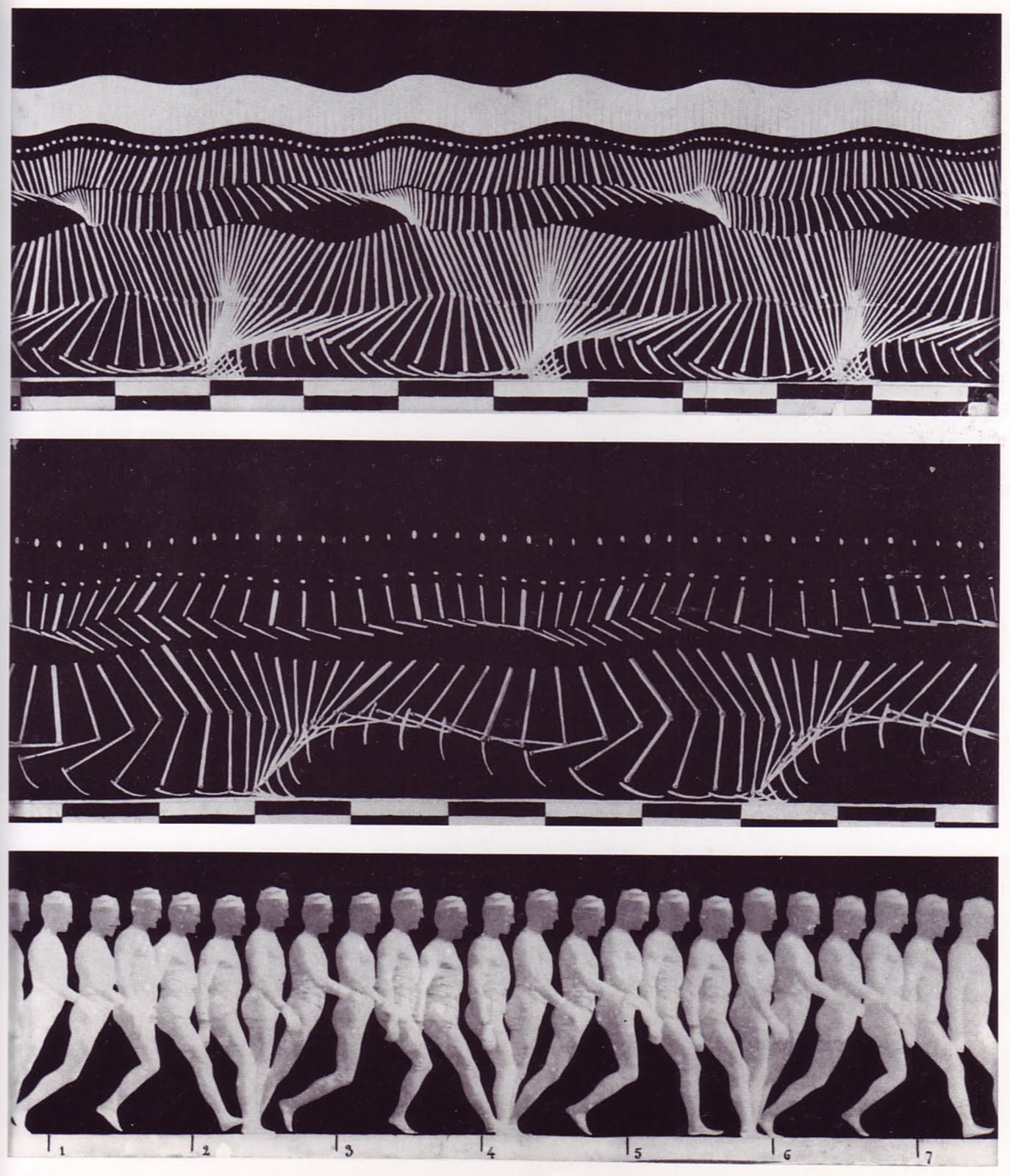

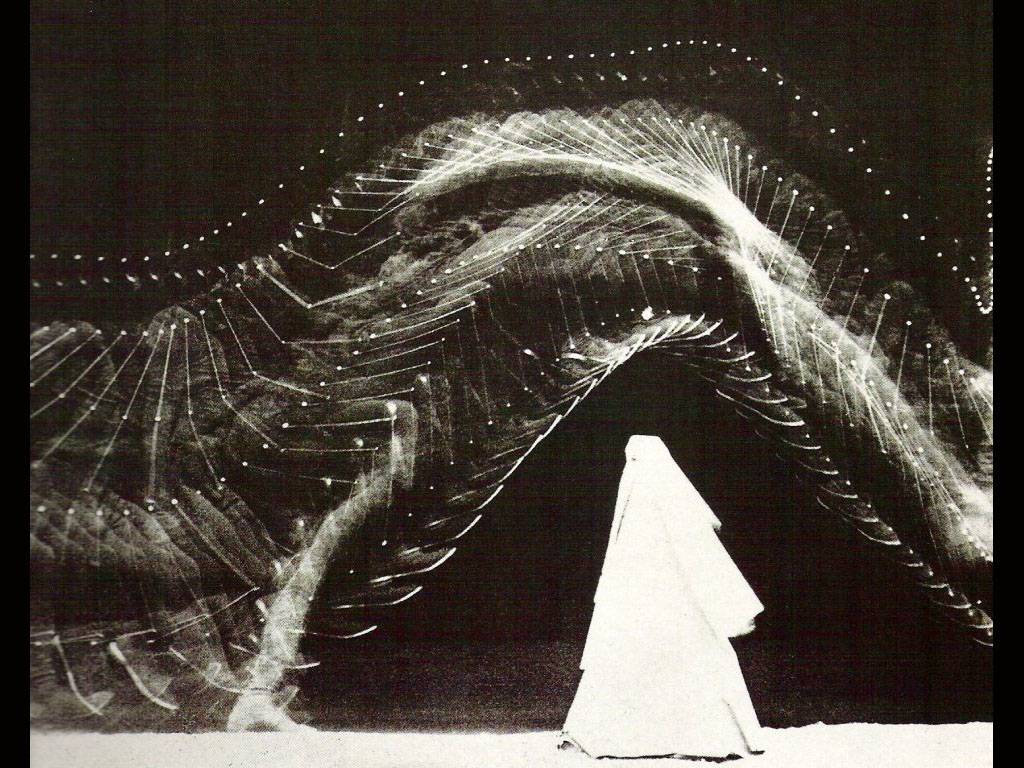

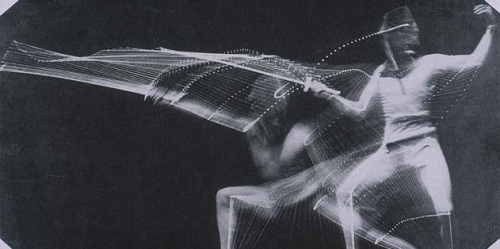

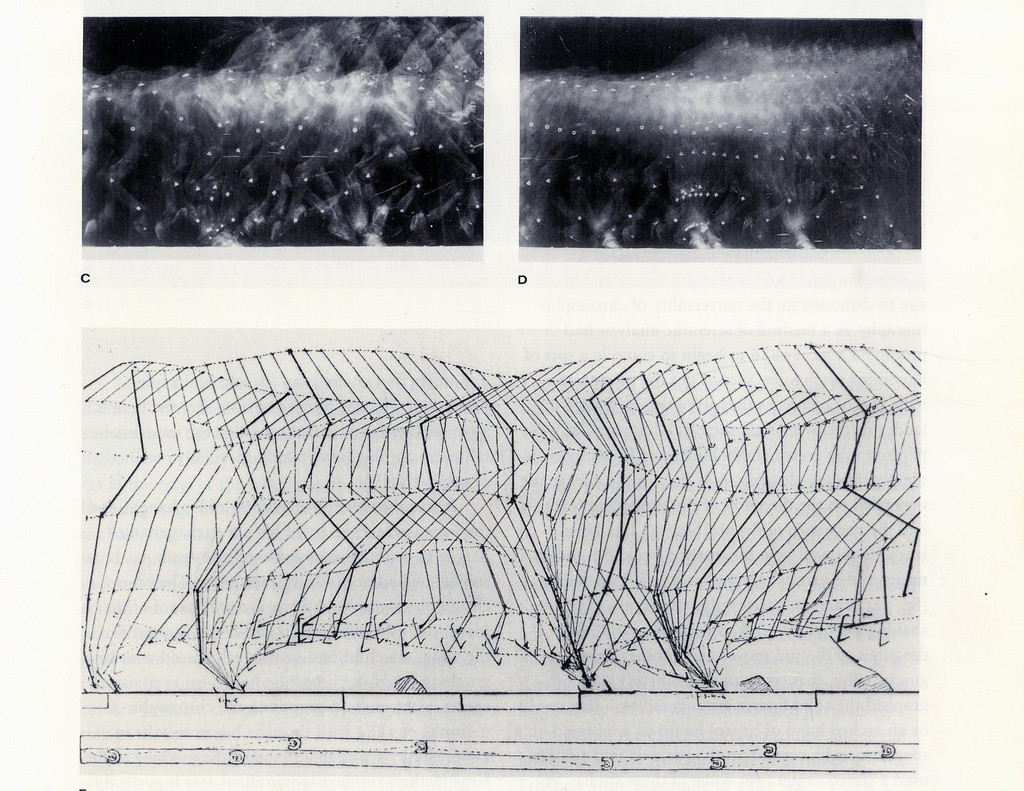

In order to exhibit these images and the motion they captured, instead of trying to create a “moving” image, Marry applied a photographic print process that exposed and over-layed all of the images onto a single print. While these images were “still”, they demonstrated a dynamic sense of motion and energy - I would argue that these images convey more movement than some videos today. They were also closer in format to the modern filmstrip run through a camera and then a projector than Muybridge’s glass discs.

Beyond these technical advancements, Marey’s direction and conceptual approaches to motion capture and exploring movement also had lasting connections to and intersections with animation (even if they weren’t all fully realized or recognized until now). The way he set up and photographed many of his subjects - in all black with white stripes against dark backgrounds - produced abstract, geometric, graphic photographs and prints that resemble something painted, drawn and/or constructed.

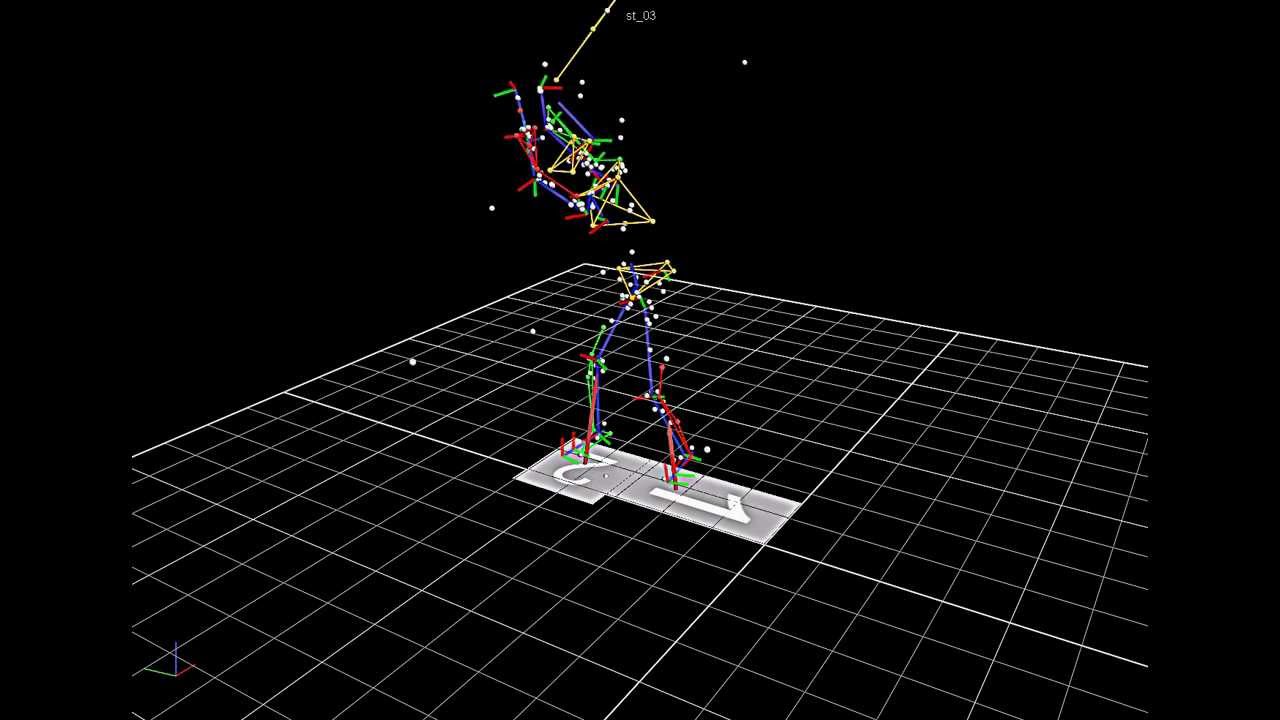

MOTION CAPTURE + “MOTION CAPTURE”

Marey’s photographic explorations with movement are similar to the motion studies and character development that animators employ today - for example, the observation methods Pixar animators utilized in order to animate the characters in the short film Piper. These setups also somewhat resemble - at the very least in concept - the “motion-capture” process employed today for digital compositing and characters that are digitally animated or enhanced, but based on human actors wearing motion-capture suits. I think it is very interesting that many of Marey’s visuals are similar to the wireframe visualizations that are often the intermediate outputs between digital motion capture and the final animation.

Early animation technologies and 3D Animation

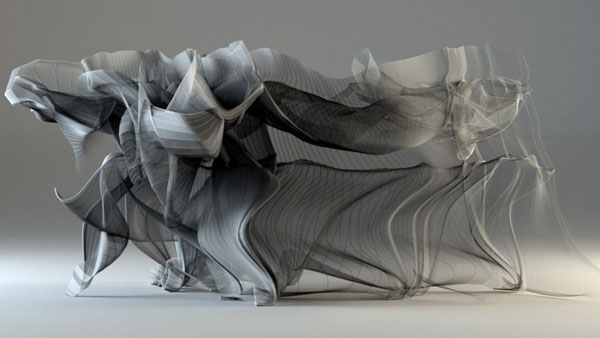

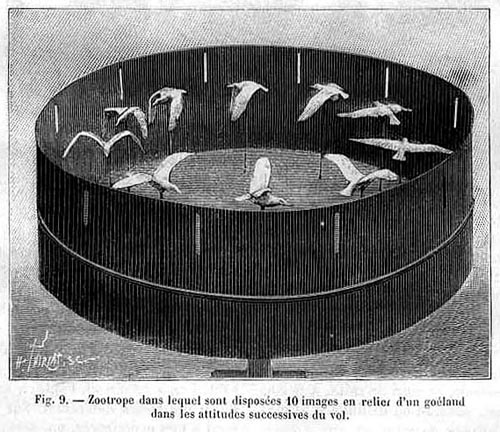

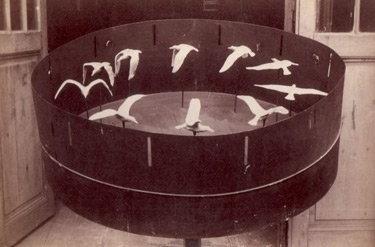

Marey also worked with Zoetrope technology - an early physical animation device that inspired the Phenakistoscope. While he did not invent this device and process, he innovated it and pushed its capabilities by creating a zoetrope drum that “animated” physical, three dimensional objects - in his case, plaster birds. With this innovation, Marey, in the 1880’s, developed a conceptual prototype for 3D animation. Presently, many 3D animation studios and animation artists are beginning to explore this technology further, pushing what is possible by using 3D printers and sometimes incorporating projection and light vector lasers. I believe this revival and new exploration of a century old device is another example of how technology in art-making is less of a straight line of progress and advancement, and more of a cyclic progression, where different processes and techniques will circle back again and again, and each time they do they are pushed and developed a but further.

Contemporary 3D Zoetrope + Phenakistoscope Discs

The examples below combine these older techniques with newer, digital production tools and techniques. These technologies include 3D printers, 3D modeling and animation, and vector-driven laser cutters.

7.5 Animation Categories, Processes and Techniques - Intro

For the remainder of this lecture, I will describe a few different types of 2D animation and some of the different tools and processes used to create these animations. For each of these examples, keep in mind there are a variety of methods - both digital and analog - that an artist can ultimately choose from to create these different animations, and that I am not going to be able to note all of them. Also remember that the majority of these types of animation were initially developed before the digital age, and that digital animation tools were heavily based on these analog production processes (and not the other way around). And finally, know that these are just general classifications and that there is a ton of overlap between different forms and animation processes.

7.6 Frame Animation / “Cel” Animation

Frame animation is the type of animation used to animate classic films and cartoons from the 1900s on, including Disney animated films. These animations are composed of thousands of still frames of drawings or paintings, each one a fraction of the movement and motion they convey. Traditionally, each frame was painted or drawn on a sheet of transparent celluloid - which is where the “cel” term comes from - so that different elements could be layered on top of one another, like a character moving on top of a still background. Each of these final frames - which might have contained multiple layers - were then composed, and photographed in order to transfer to film.

This process has obviously changed using digital tools, but the principle remains the same. Most animated gifs are frame animations, like the ones used in this interesting collaboration project. Exercise 6.1, for example, is a frame animation that also employs “rotoscoping”, which is a technique that bases illustrations directly on still film or video frames. Many contemporary animators use the frame animation process, both in analog and digital (or a combination of both) forms. Frame animation typically runs “2 up” at 24 frames per second (FPS), meaning that there are 2 identical frames running in succession for normal speed movements and actions, and then higher speed movements will be animated 1 frame at a time. This technique allows different characters or objects to easily move at different speeds within the animation - so things like jet packs and roadrunners can appear to go faster than anything else in the frame.

Below a series of frame animation GIFs made by artist Matthais Brown

The animations below are all contemporary frame animations that are compiled with digital animation software. The images themselves are a mix of hand-drawn, digitally drawn, and digitally colored or effected illustrations. Many of these animations also deal with "transformation" themes.

Rotoscoping - combining film / video and frame animation

Roto-scoping is one technique used by animators and artists to easily trace and render movement and motion filmed in real life. Conventionally, Roto-scoping is based on photographic frames of video or film - it doesn't really work to roto-scope something that is already a 2D animation (although I believe it would be possible to hand draw or trace 3D animations...hmm).

As shown in the examples below, the traces can be very precise and true to the photographic quality of the stills, or they can be heavily stylized, graphic and/or more abstract. Roto-scoping can be a useful strategy for animating complexly moving subjects, such as animals or dancers, as well as complex camera movements, where the subject might be stationary but the camera is moving through a space. When viewing these rotoscopes, consider the different styles and approaches the artists utilized.

Adobe Photoshop can be used to create short, simple frame animations. Adobe After Effects or Adobe Animate are better options for more complex or longer frame animations. Animate (previously Flash) is more lightweight than After Effects - meaning it requires less memory and will crash less - and it offers more options for creating illustrations directly within the program, however, it doesn’t provide the more advanced processes that After Effects does, and it does not have the same number of features or tools as Illustrator or Photoshop. After Effects is more ideal for importing already illustrated frames or bitmap images and then applying different processes and effects to them - choosing one over the other should be informed mostly by your personal workflow and ultimately what you are trying to achieve. After Effects and Animate are both included with an Adobe CC membership.

7.7 Stop-Motion Animation

Stop Motion animation is another form of animation that was developed in the 1900s - this type of animation has had even more cross-over and impact with the development of early motion pictures and cinema. Stop-motion animation is a type of frame animation - it too is composed of a series of still images. Instead of drawings, stop-motion animations typically work with physical objects. Each frame is composed, photographed, then the objects and/or the camera are moved slightly to compose the next frame. Some of the first “special effects” were achieved with this stop-motion process or principle, and this continued as its own industry with feature length films such as King Kong.

When many people think of stop-motion, they think of claymation or puppet-animated films such as Nightmare Before Christmas, Coraline and Fantastic Mr. Fox. Claymation / puppet-animation is a type of stop-motion where the characters, settings and scenes are made of some kind of moveable, moldable materials, and then filmed one tiny movement at a time.

These films and this style of stop motion is visually striking - it can also be a very daunting type of stop motion to start with, and it is not the ONLY kind of stop-motion. The examples below all take stop motion in different, interesting, sometimes slightly more abstract directions. I believe these examples illustrate how stop-motion can offer a more accessible way to create complex, amazing animations without the need for expensive materials and a studio set-up. I also think they all possess and communicate a visual uniqueness and style that sometimes gets lost with claymation / puppetry stop-motion.

Stop motion usually runs at “2 up” at 24 - 30 FPS. Adobe Photoshop and Adobe After Effects both have automated processes for importing photographs taken in sequence and placing one in each frame. If you are doing this in After Effects, you can then create additional animations on layers above each frame, run different stop-motion sequences together, blend 2 stop-motion sequences together, and/or apply effects to entire sequences the same way you apply effects and adjustments to still images in Photoshop. Dragonframe is another industry standard stop-motion animation program, with student rates between $250 and $200.

7.8 Tweening Animations

Unlike Stop-motion and frame animations, tweening animations can only be developed in a digital envrionment. Tweening is a type of 2D animation that automates the movement, appearance and transformation of individual pixel and vector objects over time based on keyframes. Using a program like After Effects, an objects’ keyframes are tracked, and then the frames in between the keyframes - hence the name Tween - are automatically filled in. This type of animation is ideal for animating things with lots of geometric and timed movements or transformations, such as scale shifts, rotations, x/y motion or motion along paths and applying image effects or adjustments over time.

Tweening animation is interesting because it is such a new form of animation (comparatively speaking, at least) and it has a very specific digital process tied to it. It is also interesting to explore as both a form and a technology from a development standpoint. Tweening was partially developed as a way to digitally streamline frame animations that did not require every frame to be redrawn / reshot. So, animating title sequences or text moving across an image could be done much more efficiently.

In the late 1990s, Macromedia built and promoted Flash as a way to smoothly and easily create interface animations using tweening. Artists and designers then began to use Flash to create other types of vector-based motion graphics, which made a visual space for tween animations. Adobe After Effects, which had originally been designed to add post-production effects to digital video (using tweening / keyframes to automate those effects) also started to include vector graphics support, and more artists started using it to create more complex tween animations that combined vector and pixel graphics. From this perspective, digtial tweening tools were both expediting an analog process and also directly influencing and shaping an entirely new form of animation.

For a time in the late 1990s and early 2000's, many "media-rich" websites were built with Macromedia Flash because it allowed people to create sites with functionality, animation, images and layouts that were either impossible to code with HTML, or very advanced and unstable. The website below is a prime example of a flash website - I will just say that I am glad this did not become the standard for UX/UI applications and websites.

Even though this is such a new form of animation, it is still constantly being pushed and explored, as illustrated by the examples below. Keep in mind that I have also included a few examples of frame animations created with pre-digital processes that now could be animated using tweening. These earlier artworks influenced how - and why - these digital tools were designed and now also inspire animations that are produced through this process.

Animated Film Sequences with Tweening or Tween-like Effects

Kinetic Text animations that utilize tweening concepts and effects

7.9 Back to the very beginning

To conclude this module, I want to take everyone back more than 30,000 years ago, the time period (give or take 2000 - 3000 years) that some of the oldest known drawings were created. These drawings are located in a cave in France, and were the subject of the 2010 film Cave of Forgotten Dreams.

Werner Herzog, the film's director, presents and explores these drawings from many different perspectives. One hypothesis is that these are "proto-cinematic" or "proto-animatic" images, and that the firelight that was originally used to illuminate these drawings - many of which resemble an image sequence - created a strobe that produced an illusion of motion or movement. While I imagine there is not a way to ever "prove" this, I think the drawings themselves capture and convey movement even as completely still images, and find it amazing to compare these images to the chromophotography and modern sequence images developed thousands of years later.